Bob Smillie’s Newly Discovered Prison Dossier Conjures up Questions

More than eighty years after Bob Smillie’s mysterious death in Valencia during the Spanish Civil War, his prison dossier has finally surfaced. Robert Ramsay “Bob” Smillie was a Scottish volunteer who joined the Spanish Civil War in the contingent of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and who died in 1937 under strange circumstances. Although the documents uncovered require further analysis, they allow for some preliminary conclusions about Smillie’s fate, particularly the reasons for his arrest by the Republican authorities. The dossier was found in September 2018 in the official archive of the Valencia region (Archivo del Reino de Valencia), a building that retains a multitude of historical documents going back to the thirteenth century. Among them, too, are part of the archives of the old Modelo-Celular Prison of Valencia.

As I explained in an earlier piece for The Volunteer (see the December 2017 issue), the precise circumstances of Smillie’s death are still open to speculation. This is primarily due to the lack of clarity of the Spanish institutions of the time. While official sources identified the cause of Smillie’s death in prison as natural—peritonitis—some comrades and witnesses always maintained that Smillie was a victim of the Stalinist purge in Spain and the related efforts to eliminate the POUM following the internal fighting within the Republican side in Barcelona in May 1937 (the so-called May Days).

The official version of Smillie’s death was communicated mainly by David Murray in 1937, a delegate appointed by the ILP to manage Smillie’s detention in Spain. Murray claimed that Smillie had been detained almost randomly in Figueres, at the French-Spanish border, on May 10th, 1937, when he was about to return to his country. From there he was transferred to Valencia, the Republic’s capital. Murray stated that Smillie faced several charges: he lacked proper papers when crossing the border and he was carrying war material, specifically some empty grenades. The prison dossier, however, reveals inconsistencies with Murray’s official version.

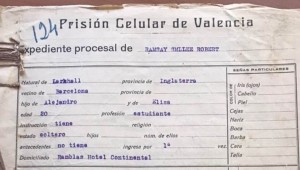

First page of Smillie’s Penitentiary File. (“Expediente Penitenciario de Robert Ramsay Smillie. Fondo documental del Archivo del Reino de Valencia”.)

What first jumps out in Smillie’s dossier is that his detention was carried out by the Spanish Republic’s Dirección General de Seguridad (DGS). The first page of the file states that on May 12th, 1937 Smillie “Enters this prison (Modelo Prison-Valencia) coming from the Dirección General de Seguridad, delivered by agents of the same Institution, as a detainee.” The file also states that his arrest warrant was linked to the arrest of a certain Domingo Aliaga Sánchez. Aliaga’s own file confirms this linked arrest.

The Dirección General de Seguridad was a public service agency, an internal national corps on which the police security forces directly depended. The Delegate of the DGS in Barcelona was Ricardo Burillo Stholle, who would be best known for his role in the repression of the POUM.

Smillie’s arrest, in other words, was by no means a casual detention at the border prompted by his lack of papers. The fact that Smillie’s detention depended on the DGS and, moreover, was linked to that of another man, suggests that his arrest was not a random event.

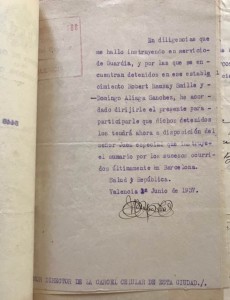

Page from Smillie’s penitentiary file. (“Expediente Penitenciario de Robert Ramsay Smillie. Fondo documental del Archivo del Reino de Valencia”.)

Murray, of the ILP, seemed unaware of this information. At least, he never spoke about it. Murray’s statement on the detention claimed that Smillie “had … a permit signed by the Commander of the Lenin Division but had unfortunately forgotten it in Barcelona.” This affirmation now seems meaningless: this kind of information would have been registered in Smillie’s prison file. It is also unlikely that in the middle of a war and with the limitations of the time, such resources and personnel would be spent on moving a detainee from the border to Valencia if his offense were merely “administrative.”

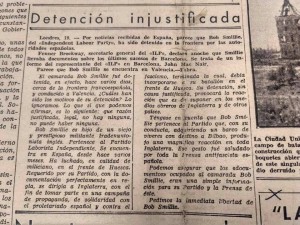

Another interesting fact to consider regarding Smillie’s detention is an article published on May 20th, 1937 in La Batalla, a newspaper associated with the POUM (and later prohibited). This article mentions that Fenner Brockway, General Secretary of the ILP, publicly stated on May 19th that Smillie, at the time of his arrest, was carrying documents about the May Days of Barcelona, specifically a report written by John McNair.

Clipping from “La Batalla,” the POUM’s newspaper, May 20th, 1937. (Archivos de la Fundació Andreu Nin.)

The reports from the prison doctor and the medical personnel at the Provincial Hospital contain the greatest number of contradictions. Smillie’s interrogation, led by the special court judging the May Days, began on June 4th. This was also the day that he began complaining of abdominal pain, according to the statement that a fellow prisoner gave to Brockway later. It seems that the prison doctor decided not to take action and Smillie continued complaining of abdominal pain during the days following.

On June 11th, a week later, the prison doctor requested transferring Bob to the Provincial Hospital because he presented symptoms of generalized peritonitis. The doctor also added: “I accompanied him to the ambulance to say goodbye, and he shook my hand. And with a grateful smile he said thank you very much.” It is hard to believe that a person in a state of generalized peritonitis and a few hours before his death was able to articulate a word or move on his own. In this same document, the prison doctor states that Smillie died on June 12th at the Provincial Hospital.

After this, the doctor on duty at the Provincial Hospital wrote that the detainee was admitted on June 11th and “hospitalized in the Surgery Service, Room number 20, bed number 315 at 20.45 hours.” The following document in Smillie’s dossier is a report typed and dated the next day, June 12th, by the director of the hospital. It states that the detainee “entered these premises on the day of today, according to the doctor who admitted him, dying thirty minutes later today as a result of appendicitis.” Interestingly, the previous document, written by the doctor on duty who received Smilie, was written one day before. Meanwhile, the cemetery record states that Smillie was buried on June 14th 1937. This date of burial is confirmed in several different documents held in the cemetery’s historical archives.

Although it is too early to draw final conclusions regarding the precise circumstances of Smillie’s death, the newly discovered prison dossier does provide new information. For one, the dates in the doctors’ reports contradict the statement on the first page of the prison file that dates Smillie’s death on June 13th. It seems obvious that some kind of medical negligence took place, but it’s doubtful that it depended only on the decisions of the doctors.

What we do know from the statements of some survivors and also witnesses, is that the interrogations carried out by the Special Services involved violent methods. Although appendicitis was often not diagnosed, leading to peritonitis and death it is also possible the “generalized peritonitis” that Smillie was diagnosed with was the result of such violent interrogations. In any case, while both negligence and abuse could be linked to this case, the dossier makes quite clear that the arrest of Bob Smillie was not accidental.

Reconstructing Smillie’s life and death is an exercise not only in memory but also in justice; it is a tribute to a young man who left everything behind to go to an unknown country to stop fascism in its tracks. As George Orwell wrote in Homage to Catalonia, “Here was this brave and gifted boy, who had thrown up his career at Glasgow University in order to come and fight against Fascism, and who, as I saw for myself, had done his job at the front with faultless courage and willingness …” Independent from this research project, Smillie will be honored in Valencia next May with a commemorative plaque designed by the Scottish sculptor Frank Casey.

Mariado Hinojosa is a writer and activist. She has published in La Directa and Nueva Cultura and is coordinator of the traveling exhibit “Espacios de memoria: las Brigadas Internacionales.”

[…] reports her discovery of the papers in The Volunteer, an online publication for veterans of the Abraham Lincoln […]

Very interesting! It was actually “Homage to Catalonia” that brought me here—I’m rather new to the in-depth details of the events of the Spanish Civil War, and, I’m afraid, new to Smillie’s life story as well. This information puts Orwell’s writing on Smillie’s death in a whole new context, and a highly important one. So I suppose Smillie died of “appendicitis” in the same way South African prisoners fifty years later would often die of “suicide”…

Thanks very much. I’m glad to have learned.

[…] Jose Medina was a Spaniard, I approached Mariado Hinojosa, an archivist/activist in Valencia, Spain. She found the evidence I needed—Captain Jose […]