The politics of Spanish resistance: Carrillo in France, 1944

Paul Preston’s new biography of Santiago Carrillo, the legendary Spanish Communist leader, stirred up serious controversy when it came out in Spain last year. It will be available in the US in February. In this exclusive excerpt, Preston recounts Carrillo’s involvement in the 1944 attempt to invade Spain from France.

Editors’ Note: Having left Spain during the Civil War, Santiago Carrillo spent much of World War II on missions for the Communist International in Moscow, New York, Cuba, Argentina, and Uruguay. In 1943 he joined the political bureau of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE), led by Secretary General Dolores Ibárruri (Pasionaria). The Party’s leadership in exile insisted on wielding authority over the Communist resistance in Spain but its lack of awareness of real conditions in the country led to frictions with the anti-Franco resistance in Spain—and to strategic mistakes such as the failed attempt to invade Spain from the north in October 1944, through the Val d’Aran. In his efforts to deny responsibility for this military disaster, Carrillo unleashed a witch-hunt against Jesús Monzón, a central figure in the Communist resistance in Vichy France during much of World War II, alongside Manuel Azcárate and Carmen de Pedro. In 1943, Monzón had returned clandestinely to Spain to create a broad anti-Francoist coalition, the Junta Suprema de Unión Nacional (Supreme Council of National Unity). The following abridged excerpt of Preston’s book finds Carrillo in the Algerian city Oran in August 1944, hoping to reorganize the Communist Party within Spain.

In Oran, chicanery by Spanish dockworkers and truck drivers saw weapons, food, and medical supplies diverted from the deliveries to the Allied forces there. Motor launches were purchased in the hope of landing guerrilla groups in southern Spain to link up with those who had been fighting there since the end of the Civil War. These were the so-called huídos, Republicans separated from their units during the Civil War who took to the hills rather than surrender. According to Carrillo’s memoirs, he planned to lead these groups himself. The implication is that, at the age of thirty, he had rediscovered the hot-headed temerity of his youth. (1)

His idea was totally unrealistic and typical of what was to be his hallmark, his triumphalist rhetoric. It is true that, within a few months of the end of the Civil War, there was a significant number of guerrilleros in rural, and especially mountainous, areas. There it was easier to hide, to avoid the patrols of the Civil Guard and even to find the wherewithal to live, if not with the help of sympathetic peasants, at least by means of hunting and collecting wild fruit. As in other twentieth-century guerrilla wars, the principal activity of the huídos was defensive, their initial objective simply survival. Unlike their Chinese and Cuban counterparts, the Spanish guerrilleros had little possibility of establishing liberated zones that might have served as bases for the future struggle against the regime. The only places sufficiently remote from the forces of repression to permit any possibility of establishing autonomous revolutionary communities were in the most inhospitable parts of the peninsula. Moreover, the depressed circumstances of the defeated Spanish left between 1939 and 1944 were hardly propitious for a revolutionary war. The repression, hunger, families destroyed by death and exile and, above all, the intense weariness left by the titanic struggles of the Civil War ensured that there would be no popular uprising in support of the huídos, who were condemned to a hard and solitary existence.

PCE safe house in Toulouse, 1949. Back row: Enrique Líster (far left, sitting on wall) and the guerrilla leader Luis Fernández (far right, sitting on wall) Front row: Santiago Carrillo (centre) and Carmen de Pedro (right). Photo courtesy of Irène Tenèze.

Occasionally they were able to emerge from their defensive positions. Attacks were carried out against Civil Guard barracks, local Falangist offices, and Francoist town halls. It is absurd to suggest, as Enrique Líster did in 1948 and the official Party history was still doing in 1960, that the guerrillas had sufficient troops to prevent Franco entering World War II on the Axis side. Nevertheless, the activities of the huídos were a constant irritant for the regime.(2) In so far as the controlled press mentioned their activities, it was to denounce them as acts of banditry and looting. However, in some rural areas, the activities of the guerrilleros had the effect of briefly raising the morale of the defeated population until the savage reprisals of the forces of order took their toll on popular support.

Carrillo’s euphoric idea of using units from North Africa to link up with the existing guerrilla groups and spark off a national uprising was utterly unrealistic. To go into Spain, he needed authorization and, initially, he was out of contact with the main PCE leadership centers in both Latin America and Moscow. However, via Russian representatives in Algeria, he managed to inform Dolores Ibárruri—the Party’s Secretary General—of his plan. She approved of the spirit behind it but was totally opposed to his participation in an incursion into southern Spain. Instead, since Paris had been liberated on August 25, 1944, she ordered him to go to France and establish links with the leadership of the PCE there.(3) He claims that he stowed away on a French warship in order to reach Toulon. He then took a train to Paris. The emaciated and unshaven creature that showed up at the headquarters of the French Communist Party was unrecognizable as the previously chubby Carrillo. He claimed that he had lost much weight as a result of poor nutrition in Algeria and the lack of food during the days hiding on board the warship and the 15-hour train ride to Paris. It is not known exactly when he arrived in the French capital but it was certainly well before the second week of October. In his memoirs, he asserted that, on arrival in Paris, he was told by the French leadership that an invasion of Spain had begun through the Val d’Aran in the Pyrenees. In fact, the invasion did not begin until October 19 and his claim makes no sense other than as part of a retrospective fabrication of an heroic role for himself in what was about to take place.(4)

It was understandable that thousands of Spanish maquisards who had been prominent in the French resistance had responded to progressive German collapse by moving towards the Spanish frontier, hopeful that Franco might be next. In his memoirs, Carrillo claimed that on his arrival at PCE headquarters in Toulouse he learned from Azcárate and Carmen de Pedro that the Agrupación de Guerrilleros Españoles had received orders for the attack through the Pyrenees from the Junta Suprema de Unión Nacional. Of the Junta, he would sneer 50 years later that it “existed only in the imagination of Monzón.” He forgot that, at the time, it certainly existed in the imaginations of Pasionaria, Vicente Uribe, and the rest of the PCE politburo, including himself. Indeed, his ostensibly cordial correspondence with Monzón both before and after the invasion suggested that he also believed firmly in the Junta Suprema. […].

In his memoirs and in reports to Pasionaria in 1945, Carrillo alleged that the Junta Suprema’s orders were the only basis for the over-optimistic and inadequately prepared operation. It is true that, in late August 1944, Monzón had sent the delegation in France an order for an invasion, albeit without specifying where it should take place. Flushed with the success of Spanish guerrillas against German units and underestimating the considerable social support enjoyed by Franco, the PCE both in France and in Moscow received the idea enthusiastically. On September 20, Pasionaria herself had published a declaration hailing the guerrilla as the way to spark an uprising in Spain.(5) Given his own contact with her, it is impossible that Carrillo could have been unaware of her enthusiasm for the guerrilla which, in any case, coincided with his own. Unsurprisingly, when Carmen de Pedro and Manuel Azcárate went to Paris in early September to discuss Monzón’s order with the leaders of the French Communist Party, André Marty and Jacques Duclos, no objections had been raised.(6)

Carrillo’s later claim that he learned of the invasion only after it had started is false. Once Monzón’s subordinates in France had decided on the venture, it was organized virtually as a conventional military operation with little by way of security. Its preparation was an open secret, with recruiting broadcasts by Radio Toulouse and Radio Pirenaica from Moscow. Before leaving for the south of France, some guerrillero units were the object of public tributes and large send-offs by the people of the French towns and cities where they had participated in the resistance. The PCE ordered its organizations in the interior of Spain to prepare for an immediate popular insurrection. The Franco regime was fully informed of what was imminent by its own agents as well as by the Communist press and broadcasts about “the reconquest of Spain.”

Manuel Azcárate wrote later that, when Carrillo arrived in the south of France, “his intentions towards Monzón were malicious. He wanted to ensure at all costs that Monzón’s indisputable achievements should not receive the credit that they deserved.” In fact, far from opposing Monzón’s illusion that an incursion of guerrilleros would trigger a popular insurrection against Franco, Carrillo shared it.

Indeed, he hoped to take some, if not all, of the credit. […] Monzón was far from alone in his readiness to risk the PCE’s greatest asset, its thousands of battle-hardened maquisards, in a conventional military confrontation with Franco’s forces. After all, with the Germans facing defeat, it was an attractive option. Carrillo, as his account of his preparations in Algeria suggested, may have also favored a strategy of starting a guerrilla war by sending small groups into Spain over a long period. Nevertheless, his fictionalized account of the origins of the Val d’Aran operation dramatically exaggerates the differences between himself and a supposedly out-of-control Monzón. As Pasionaria’s response to Carrillo’s own plans for a smaller-scale invasion from the south had indicated, the idea of a guerrilla war was approved by the PCE leadership in Moscow as well as by the delegation in France [..]. Carrillo’s attitude towards Monzón can be understood only in terms of his own burning ambition.

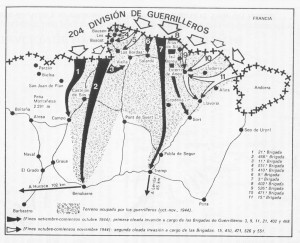

The detailed military planning of the invasion was the work of the Spanish heroes of the French resistance, Luis Fernández and Vicente López Tovar. Beginning on October 19, 1944, approximately 5,000 men of the invading army began to enter Spanish territory through the Pyrenees with the principal attack focused on the Val d’Aran. Snow-covered for most of the year and sparsely populated, it was an area of shepherds and woodcutters, a place barely appropriate as the base or foco of a popular uprising. Despite the ostentatious military structure set up by the Communist leaders of the maquis, the invasion was essentially improvised. It disregarded the obvious fact that a conventional military incursion played into the hands of Franco’s huge land forces. Nonetheless, over the next three weeks, the invaders chalked up a few successes, some units penetrating over 60 miles into the interior. In several individual actions, they roundly defeated units of the Spanish Army and held large numbers of prisoners for short periods. In the last resort, however, 40,000 Moroccan troops under the command of experienced Francoist generals […] were too much for the relatively small army of guerrilleros. […] The invaders’ hopes of triggering off an uprising were always tenuous. Deeply demoralized, the Spanish left inside Spain had still not recovered from the trauma of defeat, was ground down by fear of the daily repression and, finally and most importantly, was only distantly and vaguely aware of what was happening in France. The regime’s iron control of the press and the minuscule circulation within Spain, at least, of Monzón’s clandestine broadsheet La Reconquista de España ensured that the guerrillero invasion took place amid a deafening silence.

Rafael Alberti and Santiago Carrillo at the Casa de Campo in Madrid. 1978. Photo Nemo. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Carrillo claims that, when he heard of the operation in Toulouse, he drove frantically to the Val d’Aran to try to stop it but unfortunately found that the invasion had already started. He must have been one of the few people in France or indeed in the PCE leadership in Moscow not to have heard about it, all the more so since he had been in France for several weeks before the attack was launched. It is much more likely that he went to Aran with the intention of sharing the glory if the operation were a success or being in a position to blame Monzón if it were a failure. In his fanciful reconstruction, acting on his own initiative he was able to persuade the leaders that he had been sent by the PCE leadership in Moscow to convince them that the entire operation was madness. There is little doubt that he was acting on his own initiative, and there is reason to suspect that his intention was not so much to prevent a failure as to undermine the position of Monzón. The enthusiastic cooperation of the French resistance ensured that the invading forces were initially well equipped with supplies of food, fuel, light arms, ammunition and vehicles, most supplied by the Allies. However, they were massively outnumbered and outgunned, especially once their ammunition began to run out. The guerrilleros of the invading force were already on the point of retreat and needed no persuasion from Carrillo.

When Azcárate and Carrillo arrived at the border on October 28, the guerrilleros had already been ordered to withdraw by Vicente López Tovar, the field commander. López Tovar stated later that Carrillo did not order the retreat but rather had to be convinced to approve what had already been decided. In any case, the evacuation could certainly not have been organized overnight. Carrillo’s claim that he personally had averted a disaster was an extreme fabrication. The number of casualties as a result of the fighting in the valley was relatively small, fewer than thirty.(7) Nevertheless, at the end of the month, Carrillo sent a telegram to Pasionaria in which he claimed to have prevented the capture of 1,500 guerrilleros, stated that the preparation of the invasion had been defective and added that he planned to investigate those responsible.(8)

The rewriting of the Val d’Aran episode was the foundation stone of Carrillo’s efforts to establish himself in the eyes of most militants in France and Spain as the real representative of the Party leadership. Since Monzón had effectively rebuilt the PCE in both countries, with control of a substantial guerrilla force in France and with an enviable network of contacts with other groups inside Spain, this was no easy goal. Having ingratiated himself with the activists at Montrejeau, Carrillo now began the real witch-hunt against Monzón. Taking advantage of the absence of the senior exiled leaders, he seized the opportunity to replace Monzón’s subordinates with his own loyal followers who had enjoyed a comfortable war in Latin America […]. The condemnation of Monzón, the only significant leader who had stayed behind, and the gradual elimination of the heroic militants who had kept the PCE alive in France helped mitigate their own discomfort about their own flight from Europe. In their eyes, those who had been in the German camps and in the guerrilla war were suspect. […]

On February 6, 1945, Carrillo dispatched a report to Pasionaria in which malice and invention sat side by side. He described the PCE’s situation in such wildly optimistic terms as to make it seem that the overthrow of the regime was imminent. By implication, if this had not happened, it was Monzón’s fault for failing to link up the many groups all over Spain allegedly ready to rise up. He claimed that the Junta Suprema was “continuing to grow in popularity and prestige.” He went on to give an entirely mendacious account of the Val d’Aran episode in which claimed that the guerrilla leaders had not wanted to take part and did so only out of reluctant obedience to Monzón. He praised himself for avoiding a bloodbath. Because of Monzón’s poor preparation of the invasion, he claimed, three valuable months had been lost that could have been used to prepare a nationwide insurrection within Spain. He then accused Monzón of running the interior delegation in a tyrannical fashion in cahoots with Pilar Soler [a PC militant in Spain who had become Monzón´s lover] and [Gabriel León] Trilla [a veteran Party member and resistance fighter] and suggested that this group was close to acting against the Party.

Carrillo provided a long list of Monzón’s faults, ranging from underestimation of the role of the masses via excessive links with the right-wing opposition to lack of vigilance regarding agents provocateurs. Carrillo said that he was sending…[an order to] Monzón to come to France. The clear implication was that, if Monzón did not obey, he would have to be liquidated: “if he resists or produces excuses, I will tell him that this means confrontation with the Party leadership. In the event of him reaching such an extreme position, the comrades there will break off all contact with him and will leave him isolated. I hope that it will not be necessary to do this but we will not shy away from anything.”(9)

Having had no reply from Monzón, Carrillo sent a cable to Moscow, reiterating his criticisms. He complained that Monzón refused to obey his instructions and was obstructing the functioning of the Party in the interior. Accordingly, he repeated that, if Monzón declined to come to France, he would be separated from the organization and the necessary measures would be taken.[…] Monzón finally set off for France accompanied by Pilar Soler. En route, he was obliged by illness to delay in Barcelona, where he was arrested on June 8,1945 by the Francoist police as part of an operation that had been long in the making. With characteristic malice, Carrillo later suggested that Monzón had engineered his own detention in order to avoid having to explain the invasion. This was nonsense but may have reflected Carrillo’s concern that Monzón had turned himself in to avoid being murdered. Certainly, General Enrique Líster claimed that the person who was sent to guide Monzón over the Pyrenees had been ordered by Carrillo to kill him. Francoist versions have suggested that he was betrayed by the Party itself, which is also possible. Given Monzón’s record in Spain, once he was in custody the death sentence was hanging over him. It is thus significant that, despite his seniority in the PCE, the leadership failed to organize, as was normal in such cases, an international campaign of protest.(10) Carrillo’s loyal team of hardened apparatchiks would play a key role in eliminating those who remained loyal to Monzón and those who questioned Carrillo’s authority. […] Meanwhile, the assault on Monzón’s reputation took another turn. His partner Pilar Soler had eluded arrest in Barcelona. She managed to get to France. In the words of the Party forger Domingo Malagón, “she appeared in a black dress, like a reproduction of Dolores [Ibárruri] only rather younger.”(11) She was detained for three months in solitary confinement in a Party safe house. She was subjected to interrogation by Carrillo, Claudín, and Ormazábal and feared for her life. They demanded that she write a report on Monzón’s “deviations.” In fact, for security reasons, Monzón had told her little of his activities, and her work for him had largely been as a messenger (correo). When none of the versions that she produced met their needs, they forced her to sign a text that they had drawn up.(12) […] The information gathered was distorted and used to compile various reports accusing him of maintaining friendships with reactionaries, womanizing, homosexuality and sybaritic habits and alleging that, in prison, he was able to pay for a life of bourgeois luxury. Some of these farcical accusations were followed by faked signatures. They contained praise for Carrillo, who was thanked for apparently opening the eyes of the denouncer to Monzón’s infamy.(13)

While Monzón was in prison awaiting trial, there was an attempt on his life by Communist prisoners. Shortly afterwards, he heard that he had been expelled from the PCE. After innumerable delays, he was tried on July 16, 1948 and sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment. He escaped execution thanks to testimonies on his behalf by the Carlist leader Antonio Lizarza, whose life he had saved during the Civil War, by the Bishop of Pamplona Marcelino Olaechea and by the Captain General of Barcelona, José Solchaga, a Carlist friend of his parents. […] Monzón was released in January 1959 and died in October 1973.(14) According to Líster, Monzón’s crime in the eyes of Carrillo was not just that he stood in his way but also that he had displayed bravery in both Spain and France during World War II while Carrillo was in comfortable exile.(15)

Paul Preston is Príncipe de Asturias Professor of Contemporary Spanish History at the London School of Economics and Director of the Cañada Blanch Centre for Contemporary Spanish Studies. The Last Stalinist, his biography of Santiago Carrillo, can be pre-ordered here.

1 Moran, Miseria y grandeza, pp. 96-7; Carrillo, Demain I’Espagne, pp. 80-3; Carrillo, Memorias, pp. 394-406; Claudln, Santiago Carrillo, pp. 76-8.

2 Enrique Lister, ‘Combates y experiencias de la Agrupacion Guerrillera de Levante’, Nuestra Bandera, No. 24, January-February 1948, pp. 25-32, and ‘Lessons of the Spanish Guerrilla War’, World Marxist Review, February 1965, pp. 35-6; Ibarruri et al, Historia del Partido Comunista de Espana, p. 220.

3 Dolores Ibarruri, Memorias de Pasionaria 1939-1977: mefaltaba Espana (Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, 1984) pp. 86-7; Carrillo, Memorias, pp. 407-10.

4 Carrillo, Memorias, pp. 411-13.

5 Carrillo to Monzon, 27 July,Monzon to Carrillo, 2 August 1944, AHPCE, Caso Monzon, Correspondencia/Sign. Jacq 10. Adela Collado was the partner of Manuel Jimeno, one of Monzon’s closest collaborators – Mariano Asenjo and Victoria Ramos, Malagon: Autobiografia de un falsificador (Barcelona: El Viejo Topo, 1999) p. 103.

6 Dolores Ibarruri, ‘El movimiento guerrillero vanguardia de la lucha por la reconquista de Espana’, 20 September 1944, AHPCE, Dirigentes/Dolores Ibarruri/ Escritos, 16/2.

7 Azcarate, Derrotasy esperanzas, pp. 281-7; Fernandez Rodriguez, Madrid clandestino, pp. 334-43; Fernanda Romeu Alfaro, Mas alia de la utopia: Agrupacion Guerrillera de Levante (Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2002) pp. 25-6; Ruiz Ayucar, El partido comunista, pp. 80-1;Carrillo, Memorias, p. 413; Claudin, Santiago Carrillo, pp. 78-9; Carrillo, Demain lEspagne, pp. 95-8.

8 Telegram from Carrillo to Ibarruri, October 1944, AHPCE, Dirigentes/ Santiago Carrillo/Dirigentes – Correspondencia – Movimiento Guerrillero/Microfilm/Sign. Jacq. 9.

9 Carrillo, Report to Ibarruri, 6 February 1945, AHPCE, Dirigentes/ Santiago Carrillo/Informes/Caja 30, carp. 1.2.

10 Moran, Miseria y grandeza, pp. 102-7; Martorell, Jesus Monzon, pp. 157-64; Taguena Lacorte, Testimonio, p. 541.

11 Asenjo and Ramos, Malagon, p. 150.

12 ‘Informe de Pilar Soler sobre la Junta Suprema de Union Nacional y sobre Monzon’, December 1945, AHPCE, Caso Monzon, Informes/ Jacqs. 84, 85, 86, 87, 88 and 89; Pilar Soler interview with Emilia Bolinches in 1998; Arasa, La invasion, p. 381.

13 Fernanda Romeu Alfaro, El silencio roto: mujeres contra elfranquismo (Madrid: Edition de la autora, 1994) pp. 154-5; Martorell, Jesus Monzon, pp. 183-90; Arasa, Anos 40, p. 300; Carmen de Pedro, Report on Monzon, Toulouse, 5 August 1945, AHPCE, Caso Monzon/Caso Monzon/Jacqs. 46 and 47.

14 Fernandez Rodriguez, Madrid clandestino, pp. 347-60; Arasa, La invasion, pp. 373-87; Arasa, Anos 40, pp. 294-7; Martorell, Jesus Monzon, pp. 172-82; Moran, Miseria y grandeza, p. 106.

Thanks for the article. I was unaware of even the fact that this military offensive even occurred. While not surprised at the betrayals and set ups, I am thankful to have learned about this .

The snippet published here is disturbingly filled with sneer and innuendo. Is there a less attack-dog version of this? I know nothing of Santiago Carillo’s actions in the period. What guidance and direction was the Communist international providing? Did it approve of the 44 attempt?