An English nurse in Spain

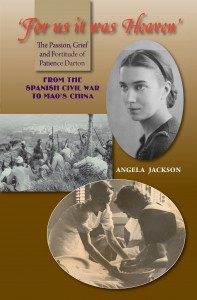

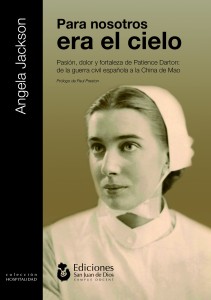

(Editor’s Note: The following article is based on extracts from the biography ‘For us it was Heaven’: The Passion, Grief and Fortitude of Patience Darton from the Spanish Civil War to Mao’s China (Sussex Academic Press, 2012, published in Spanish as Para nosotros era el cielo by Ediciones Sant Juan de Dios, Campus Docent, 2012. Buy at Powells and support ALBA.)

(Editor’s Note: The following article is based on extracts from the biography ‘For us it was Heaven’: The Passion, Grief and Fortitude of Patience Darton from the Spanish Civil War to Mao’s China (Sussex Academic Press, 2012, published in Spanish as Para nosotros era el cielo by Ediciones Sant Juan de Dios, Campus Docent, 2012. Buy at Powells and support ALBA.)

Hemingway is a great burly chap with a thick neck and a roll of flesh round the back of it. He is charming and humble – seems really so. He had a jaw wound in the Great War and has a hesitation in his speech. He can’t say what he wants to say and he talks just like his books, in bursts.

Patience Darton must be one of the few people ever to describe Ernest Hemingway as “charming and humble.” She recorded her impression of him in a letter written from Valencia after meeting him there in the spring of 1937. No doubt he had been pleased to meet an attractive, blonde, English nurse, eager to listen to his opinions, and was on his best behavior.

Patience had volunteered to go to Spain as a nurse through the Spanish Medical Aid Committee in London, feeling that as a nurse, she could “do something” to help the people of the Republic in their fight for social change. Though she had grown up in an upper-middle class family with no involvement in party politics, she had seen extreme poverty while working as a midwife in London’s East End and knew that in Spain, hard-won reforms were under threat from a right-wing rebellion led by General Franco. Patience was sent out to Spain almost immediately by the Committee to undertake the urgent task of nursing Tom Wintringham, the Commander of the British Battalion, who had been wounded and was seriously ill in ‘La Pasionaria’ hospital in Valencia.

When Tom Wintringham’s condition improved, largely thanks to good nursing care, Patience had time to meet some of the writers and intellectuals visiting Valencia. Amongst those she met was the English poet, Stephen Spender, “a beautiful creature,” who was visiting a friend from the International Brigades in hospital. An undated note accompanying a letter she sent home in March 1937 tells of one particular encounter with Spender and the well-known American writer, Ernest Hemingway, over a café cognac. Apart from her candid description of Hemingway quoted above, she wrote that their conversation ranged over ‘their own books and everyone else’s books and life and love’. Stephen Spender lamented that he could only write of past things and not of reality. He wondered if he would find reality in Spain at war. Patience carefully noted Hemingway’s reply.

Hemingway said no – you think you find reality, because you think you’re up against elemental things, but it’s like squeezing a lemon on an oyster. At first the oyster reacts and shrinks, but quickly it loses its power of reacting and the reality of the lemon ceases to be genuine.

During their long conversation, she was amazed to find that they seemed prepared to listen to her opinions.

We were talking about books and I said how much I wanted the Oxford Book of English Verse. They both agreed and Stephen said he wanted to read right through the Bible. Hemingway said “Have you ever done that? It’s a hell of a good book – you find where all the others have pinched their titles from.”

At this time, so soon after her arrival in Spain during the first days of March 1937, Patience was finding it hard work to live among people who were so deeply committed to Communism. “They live in such a different world,” she wrote, “and are so sure that they are right and everyone else criminally wrong.” It was a relief to talk to people with a different point of view.

At this time, so soon after her arrival in Spain during the first days of March 1937, Patience was finding it hard work to live among people who were so deeply committed to Communism. “They live in such a different world,” she wrote, “and are so sure that they are right and everyone else criminally wrong.” It was a relief to talk to people with a different point of view.

Hemingway and Spender were awfully kind and talked to me for a long while just as though I had as much sense as they had and I found I could speak their language and they spoke mine. Apart from that considerable comfort they were fascinating to listen to.

Patience was soon longing to be sent closer to the front where she knew her skills would be of more use. After altercations with the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, she was sent to a hospital at Poleñino on the Aragon front where other British nurses were already stationed. As the fighting moved elsewhere, there was insufficient work for them all so Patience was keen to accept an invitation to join an International Brigade medical unit. There she worked as part of a team led by the Catalan surgeon, Dr Moisés Broggi, together with the American nurse, Esther Silverstein. She now began to receive 10 pesetas a day; the equivalent of an ordinary soldier’s pay. However, American nurses with equivalent or lesser qualifications were classed as officers, and paid more, a seemingly inexplicable bureaucratic anomaly that irritated Patience somewhat.

As the war continued and battle lines moved, Patience came into contact with volunteers of many different nationalities, working in mobile units or provisional hospitals that had been set up in tents or farm buildings, even sometimes in tunnels and caves to be safe from bombing raids. By early 1938 she had experienced the horror of nursing the wounded in freezing conditions at Teruel and the terror of retreats. But she had also found joy through falling in love with a German International Brigader, Robert Aaquist. Much of their correspondence has survived; letters full of passion and ideals, and their longing to see each other during the brief times of respite between battles. By May 1938, as part of the Republican Army, the International Brigaders were undergoing a programme of training in the Priorat region of Catalonia. A new, secret offensive, the Battle of the Ebro was being planned. During these weeks, there were visits from foreign dignitaries, such as Jawaharlal Nehru, and fiestas to raise morale. Years afterwards in an interview for the Imperial War Museum, Patience recalled that May Day and one American in particular.

Patience with Jack Shafran (left) and Paddy O’Daire at an International Brigade reunion in London in 1943.

We had extra food and things sent for it, to celebrate, we decorated the place up. And we had a spitting competition. Spaniards are very good at spitting, and one of the Americans – “Tex” we used to call him – Tex was a marvellous spitter, he could aim. I don’t know how they got so much spit ready to spit with, because I dry up if I try to spit and I can’t sort of get it going. But Tex could [laughter]. He always seemed to have plenty to go and he could aim right across, so could the Spaniards – wasn’t a thing I cared for – it was quite a well known thing. And we had a target up on the side of an ambulance to be spat at, and we put the people further and further away – and they got really intent on, you know, doing better than Tex. And it was as serious as can be – we had absolute hysteria watching this because they stood there, sort of churning round with their mouths getting a good gob going then – “buong” – you see, [laughter] either booed or cheered by the surrounding crowd. It was a very good competition. Tex won.

Later on that month, Patience was irate when all her hard work and enthusiasm to make the provisional hospital run smoothly had unforeseen results. The American doctor, Bill Pike, assistant to the Chief of the Medical Services, Len Crome, considered Patience to be the best nurse to leave in charge while others went to begin new challenges elsewhere. She wrote angrily to complain to Robert.

I have been full of schemes and ideas for camilleros [stretcher-bearers]schools and organisation and what not, and got properly had. The two surgical equips [teams] that were here have moved out but left me behind in charge of the damn triage and school because there are not enough doctors so they had to leave me. Bill Pike promised to send a doctor but I feel very disgusted as the others are probably going to set up a new hospital and get more work and it is terribly dull here and now I have no one I know to talk to – that all comes of being energetic and full of ideas and not sitting still doing nothing . . .

A few days after being left behind in Marsá, Patience was ordered to report once again to Bill Pike at Valls, taking nineteen other members of the remaining medical staff with her on a supply truck. After a nightmare journey, she reached her destination and was greatly pleased to learn that she was to organise an eight-bed ambulance and the necessary assistants and stretcher bearers to go closer to the front. The following day, the journey began well, with everything stowed away tightly around the people travelling in the back, while Patience and Bill Pike sat in the front with the driver. After many hours at the wheel, Bill Pike took over so the driver could rest.

And Bill started singing as he was driving, very nasty singing which I said, “Oh God, Bill, life’s hard enough without that.” And he said, “If I don’t sing I shall go to sleep.” So I said, “All right, sing.” And I went to sleep and the next thing I knew he’d gone to sleep and we’d pitched over and I’d gone through the windscreen. And I was the only person [laughter] who could move to be hurt, all the rest were jammed tight with all the stuff they were in. He got pushed of course, in the chest with the driving wheel, but not hurt badly. I was knocked out, my face was broken up, and it looked a terrible mess. Fortunately another driver came along, English, afterwards, and we’d gone over the side of the mountain and fetched up on the only large rock sticking out, about only four foot down, so we were balancing like a comic film you see.

Patience was rescued with some difficulty due to the precarious position of the ambulance, her face covered with blood. She was taken to the civilian hospital in Valls while the others continued to the front in a replacement ambulance. She was able to write a quick note to Robert, to reassure him in case news of the accident gave him cause for worry.

Patience was rescued with some difficulty due to the precarious position of the ambulance, her face covered with blood. She was taken to the civilian hospital in Valls while the others continued to the front in a replacement ambulance. She was able to write a quick note to Robert, to reassure him in case news of the accident gave him cause for worry.

Darling unfortunately I got involved in a slight accident and got in the way of a golpe [crash] so I am staying in Valls for a week. Bill seems to think he can get a letter to you so I am sending this by him. I’m glad you can’t see me as I have two black eyes and swellings all over the place but I am quite OK but very cross at being here.

The injuries were not quite as trivial as the note implies, as a later comment reveals.

My upper lip had quite been cut right out so that you could see behind it, through to the teeth and things, and my top jaw was broken, and my nose was all over the place under one eye.

Patience fretted and fumed. The attempts to repair the damage to her face had been poorly done and the food she was given, ‘hard beans bounding around on a plate’, were impossible for her to eat.

[Laughing]And it drove me absolutely mad because my face was really in a terrible state, and they used to come in, open the door, burst into tears and go out. They brought the mayor of the place in, doing the right thing, who made a marvellous speech to say I’d now given my all to Spain, and I was furious because I couldn’t speak properly and I was bursting with the – I mean I did tell them, I had a terrible temper – that I hadn’t given my all, my face was nothing like my all, there was lots of me left, and this was a terrible way to do it and no way to treat a patient anyway.

Time passed slowly for Patience with little to do except raid packets of cigarettes she was trying to keep for Robert, write letters to him and, to take her mind off worrying about what could be happening at the front, read whatever she could find.

I shall know much more about Marxism-Leninism than you by the time I have finished being in bed as I have nothing to do but read and nothing to read but terribly serious books. I shall probably be wearing spectacles when we meet again.

In desperation, she eventually succeeded in getting to a telephone to call the Spanish Medical Aid Committee representative, Winifred Bates, who was based in Barcelona. Winifred at first did not recognise Patience’s voice as it was still so distorted by the facial injuries, but finally she grasped the words, “Hospital,” “Valls,” and “You must come and get me.” Winifred arrived the next day and, remembered Patience, “Of course, SHE burst into tears when she saw my face, it was most discouraging.” They travelled back to Barcelona together and Patience spent three days in a flat that swayed alarmingly under the heavy aerial bombardment that was wreaking havoc on the city. It was decided that Patience needed more surgery but, unlike some of the other nurses, she did not have to return to England for treatment. Luckily, she was able go to Dr Leo Eloesser, the American surgeon who had set up a clinic closer to the French border at Mataró. He was able to restore her features to a great extent, though her nose was never quite the same again.

Patience left Spain when International Brigades were withdrawn from the front, eventual arriving home in December, 1938. She continued to campaign against the policy of Non-intervention and then, after Franco’s victory in 1939, for the release of political prisoners. She was able to pass on the skills she had learned in Spain, teaching other nurses about the latest methods of dealing with war injuries. At the outbreak of World War Two she was responsible for organising medical care for Czechoslovakian refugees in Britain, then worked for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, often with the American Army. When former Brigaders from Canada and America were in London, they would sometimes visit Patience and other members of the International Brigade Association, bringing welcome treats in large food parcels. In July 1943, Patience helped to organise a very successful IB reunion in London. Among the American Brigaders present were Jack Shafran and Bill Pike. Afterwards, Bill Pike wrote to his former chief in Spain, Len Crome, to thank him for his letters and to tell him about the days he had spent in London.

In this cold damp England of yours, blast this rain and the fog, letters like yours are better than any fuel, because they last, and the glow lasts and the feeling that you are not alone stays with one and it’s a good feeling. About three weeks ago I was down in London again where I saw many of our old friends at a reunion. Nan, Patience Darton (remember when I fell asleep at the wheel, smashed the car and Patience’s nose and got 10 days arrest from you – but was permitted to go on with my work and you forgot to have the money deducted from my salary and I forgot to remind you? I still have the paper signed by you amongst my precious souvenirs), Margaret Powell (notice I mention the women first), Hans, Harry Evans, Chris Thornycroft and American lads. It was swell.

Patience never forgot the time she spent in Spain, almost two years of intense emotions that changed her life forever. Robert had been killed during the Battle of the Ebro. Wanting to carry forward his political beliefs, she had joined the Communist Party on her return to London. During the 1950s she spent four years in China working for the Foreign Languages Press. There she married another former Brigader, Eric Edney, and had a much longed-for son, giving him the name of the man she had loved in Spain.

When the invitation came for the Brigaders to return to Spain in 1996 to be awarded Spanish citizenship, Patience was already very frail and had been advised by doctors not to travel. But she was determined to go, even though she had never been back before, saying that there were too many ghosts for her there. The day after a wonderful welcome from the people in Madrid at a concert to honour the Brigaders, I was with Patience and her son when she died in hospital. She had heard the cheers of the crowd and the songs she remembered from the civil war. Without doubt, she would have thought her obituary published in Spain under the heading Morir en Madrid – To Die in Madrid after the famous documentary film of the same name, was a fitting way in which to record the close of her life.

Angela Jackson is a British historian who has been based in Catalunya since 2001. Her latest book, released in both English and Castilian, is a biography of Patience Darton, a British nurse who joined the Republican forces fighting against Franco’s rebels during the Spanish Civil War.

This is a very interesting article. I have had several e-mail contacts with historian Angela Jackson, and read some other articles by her, and this is one more of her great works. Best wishes to Angela, and to ALBA. No doubt those heroic International Brigadiers who are still alive, are, unfortunately fewer and fewer with each passing day. They were the first non-Spaniards to take up arms against fascism, and had their struggle and the struggle of Spain’s anti-fascists, been successful, Hitler and Mussolini could have been quarantined, isolated. Western “democracies” did nothing to help halt the spread of fascism in its early stages.

Remarkable woman, Patience Darton represents the best of Humanity: Love put into action in an optimal direction, where it matters most. She embraced one of the most giving activities humans can do: then helping heal the wounded in the Spanish Civil War (SCW), with the International Brigades. The SCW constitutes a drama of monumental proportions depicting a confrontation of ideas: fascism versus the will of the people of Spain and elsewhere for democracy and a better life …

Loving recognition and gratitude to Patience Darton, and many people like her who put their lives on the line in the SCW. They will be remembered and loved by the people of Spain and every community world-wide who want to see solidarity, harmony and abundance for everyone on Planet Earth.

I too found this article extremely interesting. Thus I am related by family to Patience’s beloved boyfriend Robert Aaquist.

I have the book “To us it was heaven”.

If anyone have more information about Robert I would be very interested in hearing from you. I do some genealogy research about the Aaquist-family.

Robert had a grandfather who was a younger brother to my greatgreatgreatgrandfather Olaus Aaquist. He came from Sweden as a boy with his familiy in 1814. But he and his Danish wife founded – having 11 children – the Danish branch of the family Aaquist.

Any help or information will be very helpful.

Best regards

Ole Aaquist Johansen

Denmark

oleaaquist@email.dk

I am the Speaker’s Secretary for the University of the 3rd Age in Torrevieja, and I would like it, if possible, that we could have a Speaker to. One of our Meetings, which takes place on the last Monday of the month to talk about Angela Jackson, the English nurse who was involved in the Spanish Civil War.

Many thanks.

Gillian M Burden

Telephone number – 0034 966843400

I am the Speaker’s Secretary for the University of the 3rd Age in Torrevieja, and I would like it, if possible, that we could have a Speaker to. One of our Meetings, which takes place on the last Monday of the month to talk about Angela Jackson, the English nurse who was involved in the Spanish Civil War.

Many thanks.

Gillian M Burden

Telephone number – 0034 966843400