Frank and Ajax: A Beautiful Friendship

Two Americans stand out as among the most effective and least typical of their generation to aid Spain in its fight against Fascism. Unlike most of the other U.S. volunteers who participated in the Spanish Civil War, the flyers Frank Tinker and Albert J. “Ajax” Baumler were not politically motivated men who learned to fight; they were military men who learned their role in 20th-century history.

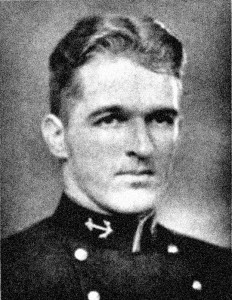

Tinker and Baumler both grew up in modest families and were in the U.S. military early in the Depression. Baumler came from New Jersey and joined the Army as a radio operator in 1933. He later got his wings, was discharged, and worked briefly as a United Airlines co-pilot before signing a contract with the Spanish government to fly for the Republic. Tinker was raised in rural Arkansas, where his father was an engineer at a rice mill. Determined to go to the Naval Academy, but from a family with no political connections, Tinker joined the Navy as an enlisted man and won admission to the Academy by examination. Graduating in the depths of the Depression, he had no Navy job waiting for him, so he joined the Army to be trained as a fighter pilot. He completed his training at the Navy’s Pensacola flight school.

Like many in Spain, Tinker and Baumler clearly saw that the civil war was a prelude to World War II, which would eventually envelop the United States. However, they did not join the Spanish Republic’s Air Force (FARE) out of idealism. Early in the war the Spanish government desperately needed trained flyers and paid well for the best.

Remember the coolly calculating character played by Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, who had made money smuggling arms to Ethiopia? But, as the Vichy-French police commander points out, “The winning side would have paid you much better.” The same held true for the two American flyers Tinker and Baumler.

Tinker grew to hate Hitler and Mussolini and foresaw the probability of the U.S. eventually being at war with them. As a result of being in hotels and movie theaters in Madrid under fire, in his 1938 book Some Still Live, Tinker writes, in our country “we may expect more or less the same thing. I can almost see the crowds standing around watching the Little Rock Fire Department dig bodies out of… hotels… and philosophically discussing the condition of the remains.”

As flyers and fighters, Tinker and Baumler distinguished themselves. They arrived in Spain and initially flew old French-built planes that were barely suited for warfare. After they proved their abilities, they were assigned to fighter squadrons flying some of the very last biplane fighters, I-15s (which look more like World War I planes than World War II) and the first monoplane fighter with retractable wheels, the Russian-built I-16, which the Spanish referred to as the Mosca (a pun based on the word for fly and the fact that the crates the planes arrived in were stamped “Moscow”).

Since both men were paid bonuses for each enemy plane they shot down, the Spanish bookkeeping was very conservative. Witnesses had to verify and wreckage had to be produced. Tinker’s officially recognized 8 “kills” and Baumler’s 4½ (indicating shared credit for a victory) are only part of the count. Tinker also had 11 “probables.”

Either way, the two pilots were the most accomplished Americans to fly for the Spanish. In 1937 they flew over and participated in some of that year’s most important battles: Madrid, Teruel, Jarama and Guadalajara. Among their accomplishments: Tinker was the first U.S. pilot (some accounts say the first anywhere) to down a Messerschmitt 109 (the Nazis’ most advanced fighter) and Baumler downed both German and Italian planes.

Neither man was a saint. They were both hard drinkers who liked to party to excess. Both had disciplinary problems in the U.S. military. Tinker had been kicked out of the Navy for brawling and lack of discipline. When off duty, they would go to Madrid and hang out with people like Ernest Hemingway. Tinker and the writer told each other tales about their exploits hunting along the White River in Arkansas. Tinker also went to movie theaters while the city was under attack and observed how cartoon characters could speak much better Spanish than he could.

Despite that limitation, Tinker briefly commanded his fighter squadron, which included Spanish and Russian pilots. How was that possible? In 1937, most planes did not have radios; cockpits were open and the commands were given by hand signals.

By mid 1937, Spain had trained enough of its own pilots and had no further need of the Americans’ services.

Upon returning home, the flyers were not greeted as heroes. They both encountered severe problems with the Passport Office and other government branches. Tinker was denied when he tried to re-enlist in the Navy. He wrote and delivered radio broadcasts in support of the Spanish government during the Civil War, although he kept his distance from some supporters of the Republic because he was unabashedly anti-Soviet. Baumler kept a lower profile and was able to rejoin the Army.

Both men kept in mind that there were more battles to be fought. When Tinker was found dead in 1939 (recent research debunks the theory that he committed suicide), correspondence about flying for China against Japan was found next to his body. Two years later, Baumler had signed up with the Flying Tigers.

Even though the White House covertly supported the Tigers, the Passport Office still gave Baumler trouble and delayed his departure for Asia. His fellow flyers were already in Burma, but he was on his way to China when the Japanese shot up his passenger plane at Wake Island on Pearl Harbor Day. He escaped injury and had to fly to China in the other direction, via the Atlantic, Africa and India. In his first victory over a Japanese plane, he simultaneously became an Ace (with 5 victories) and the first American pilot to down a plane from each of the three Axis enemies (Germany, Italy, and Japan.) He ended the war as Major Ajax Baumler.

After the war, Baumler remained in the U.S. Air Force at the reduced rank of sergeant. Was that payback for bucking the government in the Spanish Civil War, as many thought, or, as his detractors claimed, simply because of his drinking and the fact that he didn’t finish college? As it says on Tinker’s gravestone, “¿Quién Sabe?” (“Who knows?”)

Both pilots have been honored by the Spanish aviators’ organization, the Asociación de Aviadores de la República (ADAR). They are listed on its website among “Our Flyers,” and ADAR sent a medal and a Republican flag to the centennial celebration held at Frank Tinker’s gravesite in DeWitt, Arkansas. Pictures of the flyer and the event can be found here.

More information on Tinker, Baumler, and the other American volunteers who flew for the FARE is presented in a very readable fashion in John Carver Edward’s Airmen Without Portfolio (1997).

William Rukeyser is a retired reporter who grew up with stories of the Spanish Civil War. His mother, the poet Muriel Rukeyser, was in Spain on the day the war began.