From the Face of My Memory: American Women Journalists in the Spanish Civil War

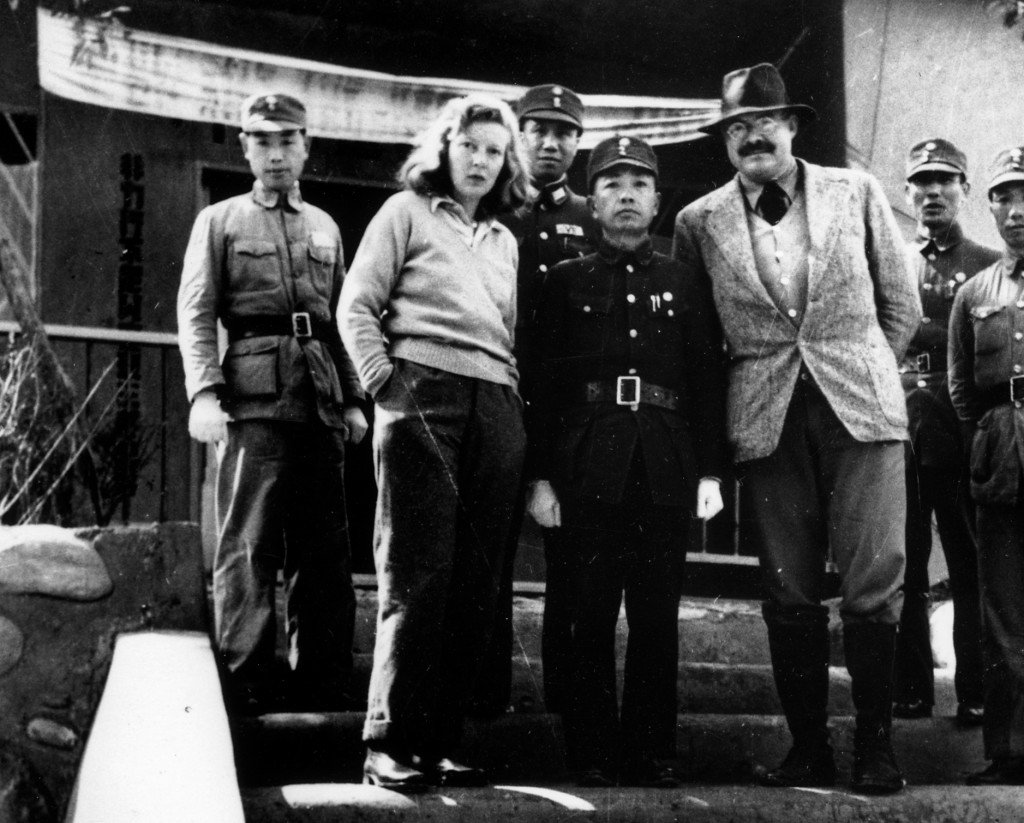

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway with unidentified Chinese military officers, Chongqing, China, 1941. JFK Presidential Library. Public domain.

The Spanish Civil War sparked the imagination and allegiance of a small group of pro-Republic American women journalists: Martha Gellhorn, Josephine Herbst, and Frances Davis. These women, displaced in war, are representative of a much larger displacement.

Faces and memory have long been associated. In his Confessions, Augustine famously used the “hand of his heart” to brush spontaneously appearing images from “the face of his memory.” We see faces like words: as parts of a whole. This partial vision is a kind of de-facement, in which we first disarticulate or displace something in order to understand it. Perhaps the largest displacement, other than death, is war. War, in all its bodily offense, is paradoxically a kind of disembodiment because it displaces us from everything that we think of as “home,” when we think of home as an embodied state of being. But what is the face of war? Dalí visualized it in 1940 as floating death in the shape of a disembodied head, a visage of fixed horror and misery, populated by similar faces reproduced in the mouth and eyes, with even tinier faces inside, the jaws of serpents snapping at the image, a picture that only the vandalism of the human soul could have produced.

The faces of war multiply, but one conflict, the Spanish Civil War, sparked the imagination and allegiance of a small group of pro-Republic American women journalists: Martha Gellhorn, Josephine Herbst, and Frances Davis. These women, displaced in war, are representative of a much larger displacement. Going beyond the physical mass dislocations of peoples, this displacement constitutes a general “structure of feeling” characterizing the period. (Structure of feeling was the phrase that Raymond Williams coined in the 1950s to refer to emerging new ways of grappling with the fluidity of experience in a changing world.) For these women, uncertainty, confusion, and awkwardness symbolically marked that displacement, suggesting that ideology and politics were not necessarily self-sufficient to explain the complex reality of their experiences in Spain.

Ernest Hemingway (back to camera) and Martha Gellhorn in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. JFK Presidential Library. Public domain.

Martha Gellhorn (1908-1998) was from a reform-minded St. Louis, Missouri family. In Madrid, her affair with Ernest Hemingway put Gellhorn in an awkward position, having arrived with a vague accreditation from Collier’s magazine. In The Face of War, Gellhorn wrote about ordinary people during war, soldiers and civilians: “what was new and prophetic about the war in Spain was the life of the civilians, who stayed at home and had war brought to them.” The walls of the Hotel Florida where she and most reporters stayed in Madrid shook daily from city bombing of a scale no one had ever seen before. The front was only 15 blocks from the hotel, in University City. You could walk to the battlefield. The war was everywhere. That meant there was no clearly demarcated space that spelled out war: “You would be walking down a street . . . and suddenly, . . . would be that huge stony deep booming of a falling shell, at the corner. There was no place to run, because how did you know that the next shell would not be behind you, or ahead, or to the left or right?” Gellhorn asks: how do we locate where war is?

Gellhorn went from place to place, creating a moving collage of memory. She wandered the streets and found houses. Some were like doll houses, with gaping fronts; some had dangling floors and the furniture blown away. They were “like scenery in a war movie: it seemed impossible that houses could really be like that.” At the Palace Hotel, now a military hospital, “one of [the men] I tried not to look at. I was afraid that I couldn’t look at him without showing it on my face.” “He was blond and young, with a round face. There was nothing left except the eyes. He had been shot down in his plane and burned . . . His face and hands were a hard brown thick scab, and his hands were enormous; there were no lips, only the scab.”

At one point, a bunch of American journalists took the day off and managed to get inside the off-limits zoo. Afterward, Gellhorn writes, “we began to talk about the war. We did not think any one would believe us when we got home, or understand, or even care. They would not know . . . how important this war was because it was like nothing else before it. We said to each other the things we already knew by heart: that we had never in one place seen people so different, so real, and so disinterested. Then we began to talk about how incredible it was to have everything mixed up together, the zoo and the gun positions behind the [Alfonso XII] statue, and the café that grew up in one half of a shelled building.” For Gellhorn, the zoo reinforces the abnormality of war: how everything is out of place, though alternatively, the war can also be seen as a normalized, confused mess. Her later reflections make transparent what was implicit: “Unexpectedly, [memory] flings up pictures, disconnected with no before or after. It makes me feel a fool. What is the use in having lived so long, travelled so widely, listened and looked so hard, if at the end you don’t know what you know?”

“We had never in one place seen people so different, so real, and so disinterested.”

Gellhorn was not alone in her uncertainty. Also a Midwesterner, the novelist Josephine Herbst (1892-1969) was born in Sioux City, Iowa. Her politics were to the left, with communist sympathies. In The Starched Blue Sky of Spain, she said, “it may have seemed to me that what I had brought back was too appallingly diffuse.” Her unpublished diary shows she wasn’t able to grasp the big picture, wavering between the personal and the political: “Write about (the truth—the terrible necessity of the truth) elusive but there, oh justice—blood and thunder stories not true.” She jotted down: “say why I am here, really, truly. To tell news, propaganda for the cause. Viper’s nest and I don’t know it.” Herbst was beginning to realize how complicated the situation in Spain was, and how challenging it might be to square justice and truth with propaganda.

Self-conscious, as “shells seem to be tearing right into the room,” she wrote, “No one notices me.” “Everyone knew where he was going . . . except me.” Herbst said: “I didn’t even want to go to Spain. I had to. Because.” “I can hardly think back upon Spain now without a shiver of awe; it is like remembering how it was to be in an earthquake where the ground splits to caverns, mountains rise in what was a plain. The survivor finds himself straddling a widening crack; he leaps nimbly to some beyond, where he can stand ruminating upon his fate.” Memory is a geological cataclysm, a shattering of everything that went before. The rupture creates the depths and heights of some obscurely fathomed change you understand has happened on a larger than individual scale that is still connected to the deepest levels of the individual.

“I can hardly think back upon Spain now without a shiver of awe; it is like remembering how it was to be in an earthquake.”

In Herbst’s memoir, the earthquake that is Spain acts as an enormous dislocation. It is easy to dismiss her comments as fuzzy thinking, but that misses the point: upheaval of this magnitude overwhelms. In the Hotel Florida, she writes, “I never seemed to be there, even when I was actually there.” “Something inside seemed to be suspended outside . . . There was a disembodiment about my own entity.” Herbst’s homeless psyche is like the Hotel Florida: filled with disembodied elements, like people constantly milling about. Her feeling of suspension recalls Dalí’s painting, in which miniature forms of death are hangared within, on an indefinite layover. Herbst also felt awkward because she had no real press assignment.

So she “did a lot of walking around, looking hard at faces”: “what had been left,” she writes, “was the aliveness of speaking faces.” An American soldier tells about the night he helped his wife deliver their baby because there was no doctor. That story and the night in the trenches “all got mixed up together.” As they walked in the dark, Herbst stumbled and he caught hold of her. “I could not see his face, only feel how he felt and that he was sorting things out from a jumbled mass of experiences if only to make some order to help him to live.” These faces of war are the face of her memory, tangled like the soldier’s experience or Gellhorn’s. But when a townsman claimed “she understands everything!”, she wrote, “I was far from understanding everything. About the most important questions, at that moment, I felt sickeningly at sea.”

Frances Davis (1908-1982) found herself in an equally intolerable position, ending up by chance in the Nationalist zone. The product of a radical utopian community, The Farm, in West Newbury, Massachusetts, by age 13 she was working as a printer’s devil at the Medford Mercury. Breaking into the business of foreign correspondent, however, proved much more difficult. Davis’s story, first published in 1940, in My Shadow in the Sun, makes explicit how out of place these women war journalists were. Like Gellhorn and Herbst, she felt she was tagging along with the men reporters: “Somewhere within me there is the cloud of discomfort at being where I am not wanted.” Davis saw herself on the outside looking in, as the men fraternized and shared information. She won them over, when she volunteered to smuggle their stories into France, by hiding them in her girdle.

A courier, she found herself ferrying between Burgos, the Nationalist headquarters, and France, leaving her in enemy territory, with “a feeling of precarious balance.” If war is an ever-present, protean displacement, here, the writer herself suffers her own physical dislocation: “I live upon the roads of Spain . . . I live in this car, shuttling back and forth . . . The car is my house, my bed, my skin. I work in my moving car, my typewriter upon my lap . . . [with] the swaying of the car as it flies over the lifting and falling and turning of the road.”

Displacement is also political: “There are the never-ending tensions of the guards . . . now my friends,” she writes; but when will they turn? Other faces, Republicans living in the Nationalist zone, “are locked against us.” Her equivocal location is symbolic of a larger question: how do we locate war ideologically? She herself was carried away for a moment when young Nationalist soldiers cried out “Long Live Spain!” She seemed caught between identities and, perhaps more disquieting for Davis, stirred, if only briefly, by the revelation that brotherhood could also be found on the other side.

Davis’s uncertain place, her “precarious balance,” means she can never quite absorb her experience. During an attack, she actually lost her balance, nearly falling on a dead body: “If I had touched that thing it would have burst. Oh, God, how close I came to touching—”. “He has been burnt and his black skin is stretched tight across his putrefied fat and muscle and insides . . . His arms stretch up to embrace my fall, skidding down the rock . . . [I]f I barely grazed that leather flesh, it would break and crumble and the gas of the putrid insides would rise and engulf me.” Her fear of touching the body speaks to the inability to articulate fully the horror of war and, more broadly, the feelings war has produced. The decomposing formlessness of “that thing” is the war, a dissolving structure that politics and ideology cannot explain. This corpse is also without a face: “He grins. He grins from ear to ear.” He joins the charred face that Gellhorn cannot look at and the unseen face that Herbst can only sense in the dark. The de-facement of war creates a structure of feeling that cannot be entirely grasped because it is displaced, like civilians without homes and soldiers without faces, but it is vividly remembered in the words of these women journalists.

Noël Valis is Professor of Spanish at Yale University. Her previous books include The Decadent Vision in Leopoldo Alas and The Culture of Cursilería. This essay has been adapted by permission from: “‘From the Face of My Memory’: How American Women Journalists Covered the Spanish Civil War,” Society (Springer Nature) vol. 54, no. 6, 2017.

so beautifully written…the passion, the adventure…we owe much…Bravo