Heroes of the Pen: Alvah Bessie on Murdered Writers, 1943

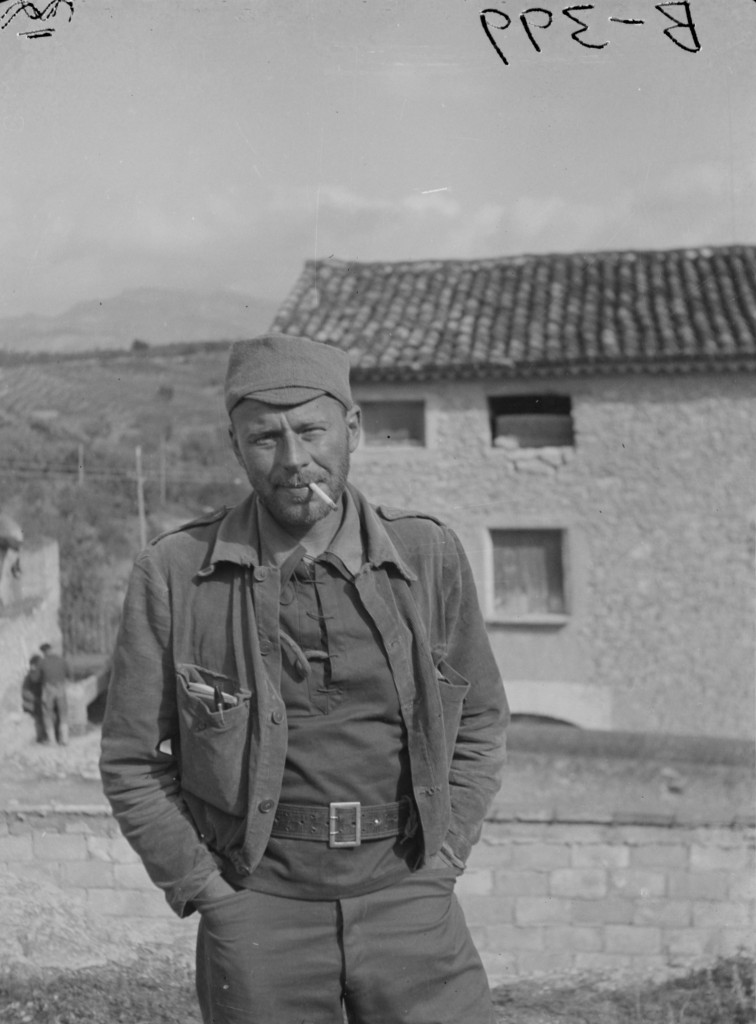

Gabriel Peri and Lucien Sampaix, two veteran writers of the Parisian pre-war Communist newspaper Humanité, were among the 100 hostages shot in late 1941 at Mont Valerien Fortress just north of Paris as one of the three “punishments” inflicted on the Parisian population by General Otto von Stuelpnagel in reprisal for the repeated bombings. Lincoln vet Alvah Bessie reported on their deaths.

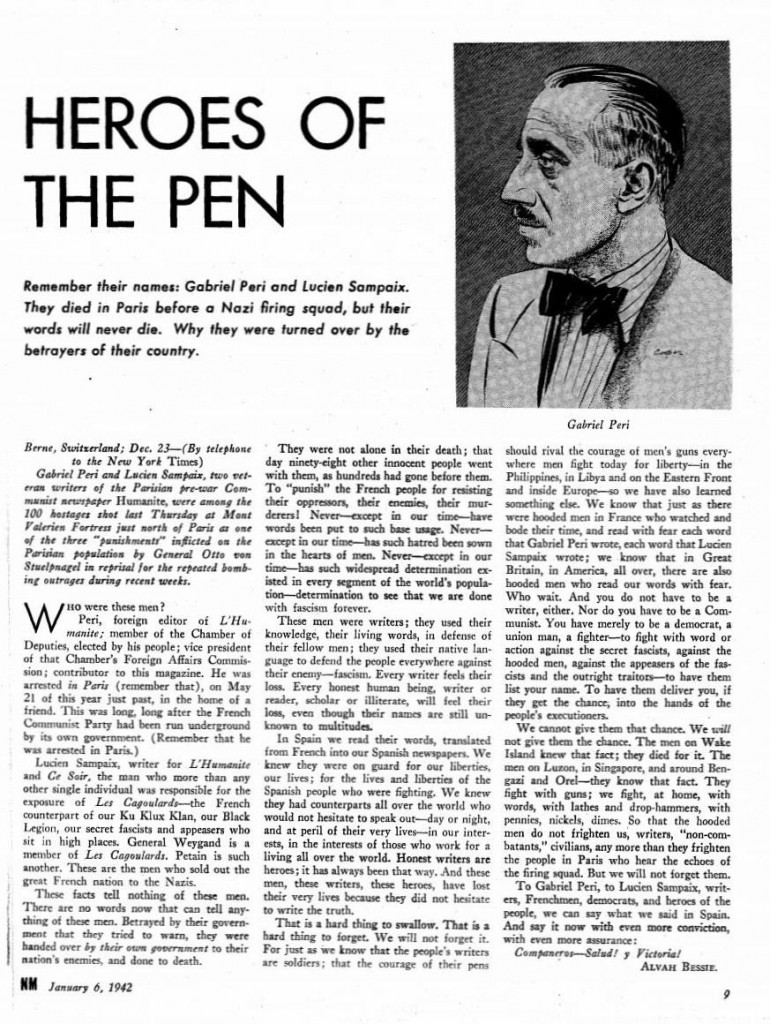

Remember their names: Gabriel Peri and Lucien Sampaix. They died in Paris before a Nazi firing squad, but their words will never die.

Who were these men?

Peri, foreign editor of L’Humanité; member of the Chamber of Deputies, elected by his people; vice president of that Chamber’s Foreign Affairs Commission; contributor to this magazine. He was arrested in Paris (remember that), on May 21 of this year just past, in the home of a friend. This was long, long after the French Communist Party had been run underground by its own government. (Remember that he was arrested in Paris.)

Lucien Sampaix, writer for L’Humanité and Ce Soir, the man who more than any other single individual was responsible for the exposure of Les Cagoulards—the French counterpart of our Ku KIux Klan, our Black Legion, our secret fascists and appeasers who sit in high places. General Weygand is a member of Les Cagoulards. Petain is such another. These are the men who sold out the great French nation to the Nazis.

These facts tell nothing of these men. There are no words now that can tell anything of these men. Betrayed by their government that they tried to warn, they were handed over by their own government to their nation’s enemies, and done to death.

Never—except in our time—has such widespread determination existed in every segment of the world’s population—determination to see that we are done with fascism forever.

They were not alone in their death; that day ninety-eight other innocent people went with them, as hundreds had gone before them. To “punish” the French people for resisting their oppressors, their enemies, their murderers! Never—except in our time—have words been put to such base usage. Never— except in our time—has such hatred been sown in the hearts of men. Never—except in our time—has such widespread determination existed in every segment of the world’s population—determination to see that we are done with fascism forever.

These men were writers; they used their knowledge, their living words, in defense of their fellow men; they used their native language to defend the people everywhere against their enemy—fascism. Every writer feels their loss. Every honest human being, writer or reader, scholar or illiterate, will feel their loss, even though their names are still unknown to multitudes.

In Spain we read their words, translated from French into our Spanish newspapers. We knew they were on guard for our liberties, our lives; for the lives and liberties of the Spanish people who were fighting. We knew they had counterparts all over the world who would not hesitate to speak out—day or night, and at peril of their very lives—in our interests, in the interests of those who work for a living all over the world. Honest writers are heroes; it has always been that way. And these men, these writers, these heroes, have lost their very lives because they did not hesitate to write the truth.

These men were writers. Every writer feels their loss.

That is a hard thing to swallow. That is a hard thing to forget. We will not forget it. For just as we know that the people’s writers are soldiers; that the courage of their pens Gabriel Peri should rival the courage of men’s guns everywhere men fight today for liberty—in the Philippines, in Libya and on the Eastern Front and inside Europe—so we have also learned something else. We know that just as there were hooded men in France who watched and bode their time, and read with fear each word that Gabriel Peri wrote, each word that Lucien Sampaix wrote; we know that in Great Britain, in America, all over, there are also hooded men who read our words with fear. Who wait. And you do not have to be a writer, either. Nor do you have to be a Communist. You have merely to be a democrat, a union man, a fighter—to fight with word or action against the secret fascists, against the hooded men, against the appeasers of the fascists and the outright traitors—to have them list your name. To have them deliver you, if they get the chance; into the hands of the people’s executioners.

We cannot give them that chance. We will not give them the chance. The men on Wake Island knew that fact; they died for it. The men on Luzon, in Singapore, and around Bengazi and Orel—they know that fact. They fight with guns; we fight, at home, with words, with lathes and drop-hammers, with pennies, nickels, dimes. So that the hooded men do not frighten us, writers, “non-combatants,” civilians, any more than they frighten the people in Paris who hear the echoes of the firing squad. But we will not forget them.

To Gabriel Peri, to Lucien Sampaix, writers, Frenchmen, democrats, and heroes of the people, we can say what we said in Spain. And say it now with even more conviction, with even more assurance:

Compañeros—Salud! y Victoria!

Alvah Bessie was an American novelist, journalist and screenwriter who fought in the Spanish Civil War and was late imprisoned and blacklisted as one of the “Hollywood Ten.” This article first appeared in the New Masses on January 6, 1942.