El Zapatero: A Memoir

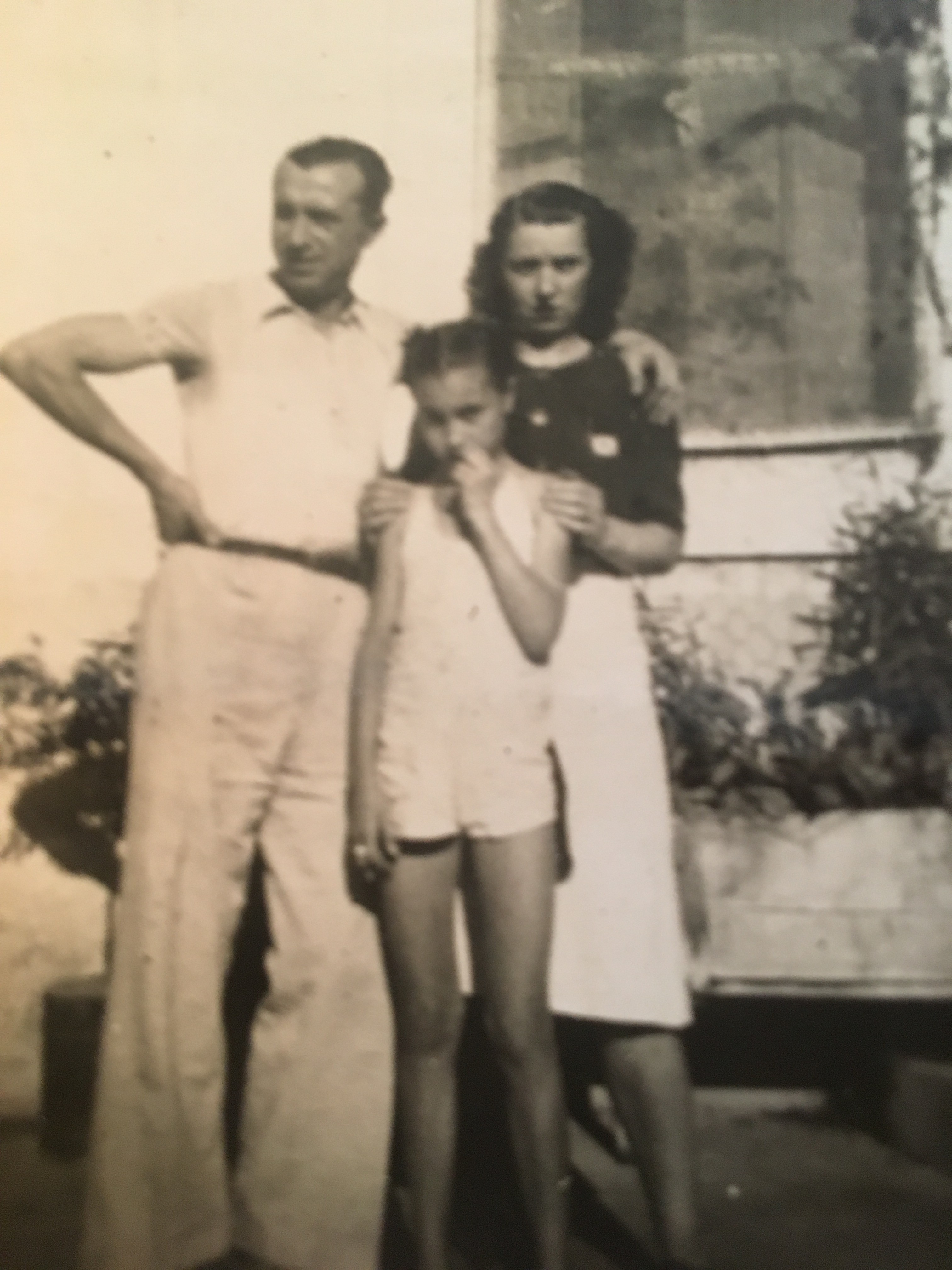

The author’s mother and her parents, Enric García Agustí and Pilar Agustí Yoller, in Narbonne, France.

A seasoned New York City reporter’s search for her family history leads her back to Civil War Spain.

I am a New York City reporter. My grandfather, a shoemaker, hailed from Catalunya. He was a Spanish Republican—a communist, a shadowy mystery I never knew. He was a crossed, tormented, silent man, pained by the Civil War, the Nazi occupation of France, and a forced exile into Bolivia in 1951. Locked out of his beloved Catalunya, he led a tortured life.

What’s more, Enric García Agustí disapproved of my parent’s marriage and therefore of my existence. He never laid eyes on me and I never heard his voice. I didn’t know whether to love him, pity him, or just see him as a person with an interesting story. I got my answer on September 11, 2001.

***

That morning the Hudson River sparkled and the Statue of Liberty stood tall and brave in the sunshine. A quiet filled my apartment facing New York Harbor. I was getting ready for work when I heard a sudden eerie back-fire blast. The thumped muffled sound turned my insides dark. Then the telephone rang.

My New York Post editor asks if I can run over to the World Trade Center. “There may be an explosion. It sounds real. Can you get down there?” I hurry out the door. Within several blocks, I stop dead in my tracks. I stand motionless with several people staring at a harmless black plume of smoke that grows darker with each second. A woman screams. “Someone fell out of a window.” I look up and see people jump. Their jackets inflate like parachutes. They descend into a cluster before they hit the pavement.

I hear a rocket engine roar. It’s thunder in my gut. It vibrates through my body. I look up to see the belly of an American Airlines jet fly over me. The plane’s wings crisscross the tower’s steel and glass for a more lethal hit before it torpedoes into the South Tower. The expected fireball is too horrific to watch. I shut my eyes and cry out for my mother, preparing to die. But instead, I feel my mother’s fearless grit. Like my mother and grandparents—survivors of the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s bombs—I am not ready to die. I open my eyes to see the orange and yellow fireball explode into a burst of black smoke.

***

It is 1937, on the hilly cobblestone street of Los Caballeros in Lleida, Spain. It is dark inside my mother’s home. It was always dark, she told me. She is seven, and my great-grandmother Tata is closing the wooden shutters of their home. A nightly practice to survive Franco’s bombardments that kills women and children recklessly while the men fight on the front.

My mother’s tummy rumbles with the usual hunger. She is numb. Death stirs through her thin arms and legs. Her sister, María Teresa, is bedridden starving to death with pneumonia. My grandmother sits vigil at her bedside watching her daughter die.

Little Pilar climbs up the three-story staircase to Tata’s room with a blanket under her arm. Tata, my great-grandmother waits to embrace her granddaughter and nestles her into her chest. Little Pilar rests her cheek onto Tata and the two begin to count the exploding bombs to gauge their distance. “Was that one far? Do you think the next one will be closer?’’ asks my mom, whose childhood innocence turns the trauma into a game. Tata gladly plays along.

Tata, the matriarch, leads the family of women. Her husband León died before the war. Her son is lost on the front. She and her four grown daughters work every surface to feed themselves. The youngest, Amparo, joins a convent. She is one less mouth to feed, but she is in peril. She is thrown into a violent religious backlash where nuns, priests and monks are killed throughout Spain. Convents, monasteries and churches from the fourth century in Lleida are burned and pillaged. Sanctuaries are destroyed now that the church is a symbol of fascist rule. Amparo never tells those horrific stories when she is alive. “¿Para qué hablar de esas cosas?’’ she said squeezing my knee to stress those gruesome years are best forgotten. “Why talk about those things?” But I am intent to research my family’s story, my curiosity spurred on by my experience on 9/11.

It’s November 1937, and Lleida lays in rubble. Fires smolder at curbsides and its cobble streets are stained in blood. Italian war planes bomb and destroy the nearby school Liceu Escolar de Lleida. Forty-eight students and several teachers are killed. Inside my mother’s home there is no light and no food. She remembers the shivering cold and laying close to the coal heater that blackens her legs and the walls of her home. A nervous anxiety inside the house fuels her hunger. To earn money and help the Resistance, my mother and grandmother work under an oil lamp and sew button holes and buttons onto Republican uniforms. The Republicans gear up to fight the Ebro Offensive a hundred miles away. The piecemeal work is as endless as the war.

Researching, I came across news reports describing the women of Lleida who march into the daylight onto the city’s ruins to chant declarations of liberty and freedom. They hand out leaflets—a manifesto that reads: “Defense Against Foreign Fascist Invaders.’’ The leaflet depicts defiant Catalan men ready to fight Franco on the Ebro and Segre rivers in Lleida and Balaguer. The leaflets call for all able-bodied men to “march to the front and halt those who are cowardly enough to give way before the claws of the Germans, Italians and Moors.’’

The Republican soldiers’ defeat at the Ebro Offensive marks the occupation of Lleida. The day Franco’s soldiers arrive, they rise the Spanish flag on the balcony of Lleida’s town hall, according to testimonies archived at the University of Lleida. “It is a pitiful sight of human life that surfaces from their shelters. They blink into the daylight to hear one of Franco’s generals give a speech. ‘I come in the name of the Caudillo [Franco] to give you bread, peace and justice.’ ‘‘

Instead, Lleida’s convents, churches, factories—even its gothic castle, Seu Vella—are turned into prisons for enemies of the new dictator. The first nine months of occupation pits friends, neighbors and acquaintances against each other. They spy on each other. Neighbors and friends denounce those who do not attend Sunday Mass; women and men suspected to sympathize with the rojos, the Reds, are sent to prison. Families of loved ones who escaped to France are closely watched. Others disappear or are killed in the street, the assassins left free to commit more killings.

Archive photos show the outside of my mother’s home barricaded by Franco’s wall of stacked sandbags 20-feet high guarded by his troops. From the city center of Lleida Franco’s soldiers fire their rifles at Republican soldiers near the Segre River. The sniper fire and lack of food and water forces civilians to flee to Barcelona or to the countryside to their farms to hide in their barns where there is food.

But my mother’s family stays put in Lleida. Mass starvation grips Catalunya. Quaker volunteers set up canteens where milk is served to children. Volunteers report that they are “working under conditions of appalling chaos and often in great personnel danger…By the end of the year mass starvation became an actuality in which the children were the worst sufferers,’’ according to a 1938 Quaker Annual Report. Food aid is confiscated by Franco’s Auxilio Social which hoards the food for themselves, according to the report.

***

The author’s mother, Pilar Agustí Yoller, and her sister María Teresa Agustí Yoller, on Palm Sunday.

Yet, my mother explained to me, life was not always bleak in Lleida. It is Palm Sunday before the war. Little Pilar and her sister Maria Teresa smile innocently into a camera lens that captures the holy day on Calle Mayor—Lleida’s commercial promenade. The two sisters are in matching dresses knitted by their mother. They flare from their knitted crochet bodices that sparkle in the sunlight like lace. Their white and black patent leather shoes and flawless white anklet socks capture the camera’s shutter light. They hold identical sachets of candy and palms. The sun lights up their long brown hair that is parted neatly in the middle and braided off their faces with crisp shiny ribbons. The girls do their best not to giggle into the camera but the joy of childhood bubbles over. There is abundance in the young family’s life whose parents met and fell in love on the very same street.

Their father, Enric, ‘El Zapatero’—the shoemaker—works in the family shop. He learns the craft of sewing fine leather shoes from his father, Pere, whose father taught him. Enric’s habitat is Calle Mayor, where Catalan businessmen operate more like artisans. Hat shops of felt berets, fabric and tailor clothing stores are intimate talleres, workshops, whose owners’ skillful hands are respected. The stone glass storefronts with its brass door handles are salons where customers and store owners conduct cordial business. Enric grew up surveying this commercial buzz and as a young man he stood in the threshold of his family’s store—elbow jutting from his waist—studying people as he drew on a cigarette. His discerning eye mirrored a confidence that suited his other job — a police officer for the Comisario de Policia de Catalunya.

Enric wore his badge proudly. (Today it is in the possession of his grandchildren in Bolivia.) He joins the Resistance, but, as my grandmother tells me 40 years later, it is not long before he is denounced when a traitor infiltrates his group. Ambushed one night after a clandestine meeting by armed men, they load Enric in the back of a truck. He knows he will be tortured, starved and brain washed—a slave to Franco’s military machine. With the noose around his neck, he plans an escape. My grandmother proudly describes Enric leaping from the truck onto a dirt road in the pitch darkness near the wooded lake district of northern Spain. He runs into the woods of the Pyrenees to hide and struggles through the brush to circumvent the pine tree valley to find the best roadside route into France. But by dawn he is spotted by French police and taken to a concentration camp. A half a million Spaniards will follow the same route less than a year later.

A cousin in Barcelona, whose father was my mother’s first cousin told me another story. Soon after my grandfather’s capture, my grandmother is inside the home of Enric’s mother. A startling loud door knock reveals three soldiers who push through the doorway. My grandmother stands next to her mother-in-law Felisa and sister-in-law Teresa. My mother and her five-year-old cousin Josep huddle in the background. They watch the women of the family face off with the soldiers. The interrogation begins. “What does Enric do for a living?” No one answers. The soldier barks again: “What does Enric do for work?’’ Pilar’s heartfelt retort: “Lo mismo que usted pero en el otro bando”: The same as you but for the other side. The soldier slaps my grandmother across the face. The idea that they share a common ground cannot be accepted by the occupiers. Pilar stands ready for another blow or worse. But the soldiers leave. My grandmother’s steadfastness reputes her as a woman of valor.

The ramifications of Enric’s capture create the need for an urgent exit. His family leaves for Barcelona. Pilar stays in Lleida to weather the dictatorial occupation and waits to hear from her beloved husband. A hand-delivered letter arrives. She learns a distant cousin claims him from a concentration camp and goes to Narbonne, a small French city of gothic churches and cobblestone streets that feel like Lleida. There Enric works in his cousin’s shoemaker shop. Industrious Catalan that he is, he opens his own store: the “Coeur de la Pomme,” the Heart of the Apple.

My grandmother reads his letter repeatedly and decides to follow her husband. Hiring a smuggler to cross into France is an expensive proposition when everyone in the house is hungry. My grandmother persists and sews at a fever pitch along with my mother who sews with needle and thimble. My mother remembers Tata arguing that an escape to France is too dangerous and reminds my grandmother she already lost Maria Teresa to the war. But there is no convincing. Enric, the love of her life, could never return to Spain.

The evening, as they leave, the smell of snow chills the air. Dressed in layered sweaters under heavy coats, Pilar, 27, now is the head of the family. In one hand she grips a small leather valise in the other she clutches my mother’s small hand. My grandmother vows never to let go. If caught they will be separated. Children are taken from their mothers and placed in orphanages under Franco’s occupying regime.

They cross the Pyrenees on foot. A string of farmers and sheep herders take them through Catalunya’s Pirineos, through the tiny villages that make up Catalunya’s Comarcas along the northern mountain footpaths. At an altitude of 2500 meters, 7500 feet, the winter wind shears through their city clothes. Moon rays bounce off the snowcapped mountains exposing them, but also guide their path.

They cross the Valle de Aran into Andorra, in the direction where Republican soldiers exchange gunfire with their enemy, rather than follow the roadside which is a target for Franco’s bombs. They hike at night and hide in the day in barns where dairy farmers feed them milk and cheese. Each step is a touch of faith in a journey that takes almost a week. I know: I retraced the hike 50 years later.

It is dawn when they reach Narbonne’s main square. My grandmother stops to wash the dirt from their clothes, legs and face and shoes with the frigid waters of the Canal de la Robine. She washes my mother’s face hoping the water will rub off the fear and uncertainty. But water cannot give my mother the love and assurance she needs. She is hungry and her heart is weary. She never wanted to leave Spain. The dawn turns into a cold cheerless morning. A man near the promenade arranges café chairs and tables. My grandmother asks directions from the letter’s address she memorized. He points them in the direction. Nervous with fear, they arrive but no one is home. A neighbor hears their knock and suggests they try a cafe where Enric has his coffee. They step out onto the damp grey cobble stones and find Enric at a table. He is with another woman. But my grandmother is not angry. This is war and jealously is a luxury. She understands her husband’s needs and knows she must reunite her family.

***

I think about my grandmother and mother’s courage as I crisscross through the side streets of Lower Manhattan to avoid police after the World Trade Center collapses. It is noon and the sun beats down hard on my throbbing head. I reach the burning inferno. There is no relief to the unfolding disaster hatched by tyrannical perpetrators who turn commercial jets into bombs killing innocent people. I pray for rain to extinguish the hell that is burning up the city.

***

As the Civil War draws toward a close, the Republic’s defeat only a matter of time, more Spanish war veterans, women, children and elderly flood into France. Refugees fall onto Narbonne’s beaches and are left to die—all walking distance from Enric’s shop. But Enric works undeterred, threading his family into the fabric of Narbonne despite the fog of famine that lingers at his doorstep. Enric’s determination to outwit death runs through me as it did through my mother, who also never felt his love. Our connection to Enric is visceral. It was his blood, steeped in political conviction, strength and spirited zeal, that rallied inside me on 9/11—a day of terror when I was alone but, like him, a step ahead of death.

Dear Maria. What a moving testimony of your family’s suffering under Franco and your witnessing the barbaric attacks in NYC>

I look forward to talking this week.

best wishes Peter