Lincoln Vet Nancarrow Gains Museum Triumph

Lincoln vet and path-breaking composer Conlon Nancarrow was among the dozens of American leftists who no longer felt at home in the United States. After moving to Mexico he began a 40-year career of composing for the player piano. In June, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art celebrated his work with a 10-day festival.

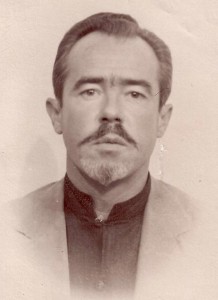

Working in near isolation from a custom-built studio, Nancarrow created some of the most mathematically complex and dramatically exhilarating music ever written. Conlon Nancarrow, June 1987. Photo Irene de Groot. CC BY-SA 3.0/GFDL

Conlon Nancarrow (1912-1997) was a composer whose unique compositional ideas are as fascinating as his single-minded approach to life. On returning to the United States after serving in the Lincoln Brigade, he was dismayed to be refused a passport thanks to an earlier Communist party membership. In 1940 he emigrated to Mexico City. There, as before in Boston, he found the musical community unable, or unwilling, to play his rhythmically complex compositions. By 1948 he had turned his back on human performers as well as his country, and began a 40-year career of composing for the player piano, punching holes by hand into paper piano rolls.

Freed from the limitations of players, he was able to pursue his interests in complex timing relationships, and became the greatest exponent of the “tempo canon”: a technique where two or more similar lines of music play at different speeds. Working in near isolation from a custom-built studio, designed by the celebrated architect Juan O’Gorman, he created some of the most mathematically complex, and dramatically exhilarating music ever written.

His studio also housed his vast private library, in which he amassed a collection of books on a broad range of subjects that any small college would be proud to have in its library. Recordings made on his antique player pianos gradually caught the attention of well-known composers who championed his work, among them John Cage and Gyorgi Ligeti. Commercial releases rapidly gained cult status and in his 70th decade he found considerable fame and modest fortune, winning a MacArthur Genius Award in 1982. Today his name is mentioned in every history of 20th-century classical music, while jazz, classical and electronic composers continue to cite him as a key point of reference.

Recordings made on his antique player pianos gradually caught the attention of well-known composers who championed his work, among them John Cage and Gyorgi Ligeti.

The recordings of his player piano works are easily obtained but the instruments they were created for are becoming rare. However, two recent high-profile festivals have valued the work sufficiently to acquire and restore such instruments: in 2012 at London’s Southbank Centre, and a 10-day celebration in June this year at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. This is not the first time his work has been recognized. In fact, the best known recordings were made by American producers and record companies. However for the Whitney to make such a bold statement of support could be seen as a poignant and quietly triumphant homecoming.

Dominic Murcott is Head of Composition at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in London. He co-curated “Anywhere in Time: A Conlon Nancarrow Festival” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in June 2015.