The Burglary: The 1971 discovery of Hoover’s secret FBI

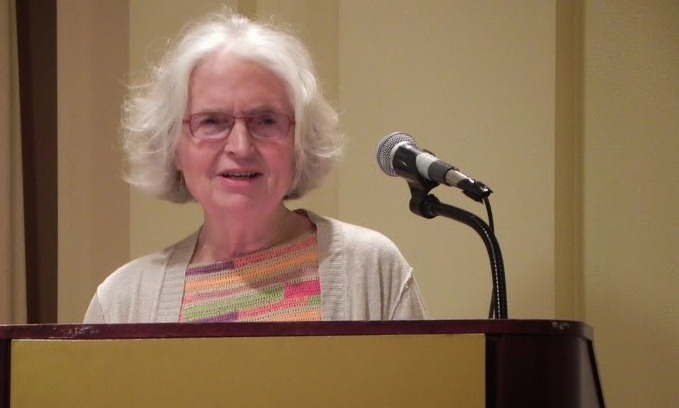

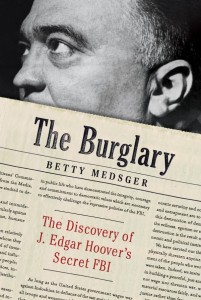

On June 6, journalist Betty Medsger delivered the annual ALBA/BillSusman Lecture, based on her recent book The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI.Medsger’s book features the never-before-told story of the history-changing break-in at the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, in 1971. The burglars were a group of unlikely activists—quiet, ordinary, hardworking Americans—who revealed a shocking truth, confirming what some had long suspected: that J. Edgar Hoover had created and was operating, in violation of the U.S. Constitution, his own shadow Bureau of Investigation. The lecture honors one of ALBA’s founders, the Lincoln veteran Bill Susman. What follows is a synopsis of her talk.

At two crucial points in history, now and in 1971, Americans learned that their intelligence agencies were out of control and engaging in activities that most citizens consider inappropriate in a democratic society. These deeply concealed secrets were made public not by investigative reporters, vigilant members of Congress, or alert Attorneys General, but, instead, by unknown citizens who risked being imprisoned for many years.

During the Cold War, in 1971, eight people burglarized the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, and revealed through journalists the first documentary evidence that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover engaged in surveillance and aggressive dirty tricks, including violent actions, against people he considered subversive, especially African Americans. In anonymous letters that accompanied the files they mailed, the eight called themselves the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI. In 2013, in post-9/11 America, former NSA contractor Edward Snowden distributed to journalists thousands of NSA files that revealed blanket surveillance of Americans on all forms of electronic communication, plans to expand the agency’s cyber warfare capability, and focused dirty tricks, primarily against Muslims.

In contrast to Snowden, the identity of the Media burglars was never known. They had promised each other they would take the secret of the burglary to their graves. Despite the fact that 200 agents searched for them for five years, the burglars never were found. And despite its enormous impact, the burglary was largely forgotten until most of the burglars stepped forward when my book about the burglary and its impact was published last January. Their story is also told in 1971, a documentary by Johanna Hamilton that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in April.

The files were removed from the small FBI office in Media, a suburb outside Philadelphia. “Just a few things missing,” local FBI officials told reporters the day after the burglary. That wasn’t quite true. Every file in the office—about 1,000—had been removed. Beginning immediately, those “few things” missing led to the start of one of the most extensive manhunts—and woman hunts—in the history of the FBI and led, by the mid-1970s, to far more: the first congressional investigations of all intelligence agencies, the establishment of permanent congressional oversight of intelligence agencies and the strengthening of the Freedom of Information Act.

The idea for the burglary came from the mind of William Davidon, a mild-mannered physics professor at Haverford College who had actively opposed the use and development of nuclear weapons since the dropping of bombs on Hiroshima. He had actively opposed the Vietnam War. Throughout 1970 people participating in the large peace movement in Philadelphia had been telling him they thought their organizations had been infiltrated by spies. As someone who disliked conspiracy theories, Davidon did not believe those rumors. But he kept hearing them from people he respected.

The idea for the burglary came from the mind of William Davidon, a mild-mannered physics professor at Haverford College who had actively opposed the use and development of nuclear weapons since the dropping of bombs on Hiroshima. He had actively opposed the Vietnam War. Throughout 1970 people participating in the large peace movement in Philadelphia had been telling him they thought their organizations had been infiltrated by spies. As someone who disliked conspiracy theories, Davidon did not believe those rumors. But he kept hearing them from people he respected.

By that fall he concluded the rumors probably were true. Most people had a helpless reaction to the rumors: “Of course it’s true, but there’s nothing you can do about it.” To them, it was a problem that was impossible to solve. How could anyone force the powerful and popular FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, to open his bureau to inspection? But Davidon thought that if it was true that the government, through the FBI, was spying on protesters in an effort to suppress dissent, it was a problem too big not to solve. He feared rhetoric without facts would deepen cynicism. He was convinced that if evidence of suppression was presented to Americans they would demand that it be stopped.

By the fall of 1970, a rather hopeless time in the peace movement, he felt there were two wars that needed to be stopped: the war in Vietnam and the war against dissent at home. Accepting the fact that no officials had investigated the FBI or could be expected to do so, Davidon drew up a list of nine people and asked each of them:

What do you think of burglarizing an FBI office?

The burglars had promised each other they would take the secret of the burglary to their graves.

Startled at first, nearly all of them eventually agreed with his reasoning: evidence must be found and given to the public in order to stop the surveillance. Only one person on his list, a philosophy professor, turned him down. Later, just days before the burglary, one member abandoned the group without explanation but with full knowledge of their plans. The remaining eight people moved forward despite not knowing if he would turn them in, as he threatened to do a few weeks after the burglary.

They faced other circumstances that surely would have stopped other people. From inside the glass front door of the county courthouse across the street from the building where the FBI office was located, 24 hours a day a security guard watched the well lit door they would enter and leave. The night of the burglary, two locks—instead of only one as viewed by two of them earlier—were on the door they intended to enter. One of those locks could not be picked, prompting the lock picker to suggest the burglary be called off. Despite these threatening circumstances, they moved ahead.

Who were these people were who took such a profound risk even though they had no idea whether they could break in without being caught or if there was even a single file inside that office that would confirm their suspicion that the FBI was suppressing dissent? For all they knew, they could have ended up in prison for stealing useless files, blank personnel forms.

John and Bonnie Raines, a couple with three children under age eight, were part of the group. John was a professor of religion at Temple University, a position he would continue to hold until he retired. Bonnie was a director of a day care center at the time. They felt strongly that parental responsibilities should not prevent people from being devoted activists—even carrying out acts of non-violent resistance that could lead to prison. They made arrangements for members of their family to raise Lindsley, Mark and Nathan if they had to serve time in prison.

Other members of the group were Keith Forsyth and Bob Williamson, both of whom had dropped out of college to work nearly fulltime to stop the war. Forsyth, a cab driver, developed his burglary skills by taking a correspondence course in locksmithing. Williamson was working as a social worker for the state. Susan Smith and Ron Durst—members of the group who have chosen not to be identified by their real names—played crucial roles in the casing that took place for three months before the burglary.

Bonnie Raines did the most dangerous casing. Posing as a student researching work roles for women in local offices, she surveyed the inside of the FBI office while interviewing the agent in charge. Her discovery that there was no alarm system in the office encouraged the group’s decision to move forward. Her face was remembered by the agents and a sketch of her likeness was issued to FBI agents. From the day after the burglary until the day he died in May 1972, Hoover frequently said, “Get that woman.”

Members of the group found courage from various sources. Outrage at the Holocaust in Europe was a key motivation for several members of the group. The courage of black people as they pushed to obtain their basic rights in the early 1960s in the South inspired courage in all of the burglars. The struggle to end the war was the primary inspiration for the youngest in the group.

“Just a few things missing,” local FBI officials told reporters the day after the burglary. That wasn’t quite true.

The date of the burglary—March 8, 1971—was not an accident. The fight of the century—the first world heavyweight boxing championship match between Mohammad Ali and Joe Frazier—was held that night at Madison Square Garden in New York. The world—literally, the whole world, was waiting for this night when Ali would return to the ring for the first time since he had been convicted six years earlier for refusing to serve in the military because of his opposition to the war. Frazier was admired by people who supported the war, including President Nixon.

The burglars thought nearly everyone would be tuned to television and radio reports on the fight—FBI agents, local police, and the residents who lived on the two floors above the FBI office. The crackling broadcast sounds, they hoped, would muffle burglary sounds. That seems to be what happened, as Forsyth, the lock picker, worked slowly with a crowbar and car jack to break in and assure that the office was ready for the four people who would work in the dark, stuffing suitcases with every file in the office.

One of Hoover’s favorite reporters wrote that Hoover was “apoplectic” when told about the burglary. None other than the future Deep Throat, of Watergate fame, was sent to the crime scene the next morning. Ironically, the burglary could not have happened except for Felt’s refusal in fall 1970 to purchase an alarm system or a large file drawer-type safe, both of which had been requested by the agent in charge of the Media office.

After 10 days reading, sorting, and collating the files at a remote farmhouse, the burglars copied files and prepared them to be mailed in small packets over the next two months. As their work ended, they made two promises: they would take the secret of the burglary to their graves and they no longer would associate with each other, fearing that the arrest of one could lead to arrest of another.

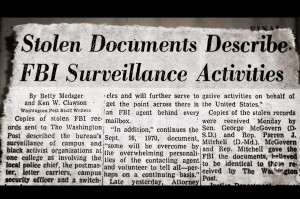

On the day after their last meeting, John Raines mailed the first set of stolen files to two members of Congress—Senator George McGovern, Democrat of South Dakota, and Rep. Parren Mitchell, Democrat of Baltimore—and three journalists—Tom Wicker, columnist at the New York Times Washington bureau, Jack Nelson, investigative reporter at the Los Angeles Times Washington bureau and myself, a reporter at the Washington Post. I didn’t know until I read the 34,000-page investigative file of the burglary many years later during research for my book that I was the only recipient who did not give the files to the FBI.

One file stood out immediately, the one in which agents were instructed to “enhance paranoia,” to make people think there was an “FBI agent behind every mailbox.” I wondered if I was holding a hoax. It seemed unlikely that an intelligence or law enforcement agency would state such extreme goals in writing.

Hoover’s FBI had African-Americans under surveillance by paid informers literally everywhere they went.

Those initial files also revealed campus spying for the FBI by paid informers: switch board operators, mail carriers, and mid-level college administrators. Among the most important revelations in that first set of files were ones that revealed Hoover’s FBI had African-Americans under surveillance by paid informers literally everywhere they went: the corner store, bars, and restaurants, as well as school and college classrooms, libraries, and churches. Every agent, the files revealed, was required to hire an informer to spy on black people. In Washington, DC, every agent was required to hire six agents to spy on African Americans. Neither violent nor subversive behavior was necessary. Simply being black was enough to attract the FBI’s watchful eyes and fill its files.

So sweeping was the surveillance revealed in the files that newspaper editorial writers wrote that it resembled the work of the dreaded East German secret police, the Stasi.

My primary concern as I finished reading these first files was: were they authentic? The FBI was eager to confirm they were. Doing so, they assumed, would convince us the content of the files should not be reported. As I wrote a story about the revelations, Attorney General John Mitchell called the two editors in charge of the story and publisher Katharine Graham, repeatedly urging them not to publish. It was the first time the Nixon administration pressed Graham to suppress a story. The second instance came three months later when the Post received the Pentagon Papers. She did not want to publish the Media files, nor did the Post’s attorney. But editors Ben Bradlee and Ben Bagdikian convinced her to do so, and the story was on the front page of the Post the next morning. After the story broke, other news organizations reported extensively on the Media files over the next three months as they were distributed by the anonymous burglars.

There was an immediate and unprecedented outcry for the FBI to be investigated, including from members of Congress and editorial boards that previously had expressed only praise for Hoover and the bureau. Senator Sam Ervin, Democrat from North Carolina, later a hero as chairman of the Senate Watergate hearings, was urged in spring 1971 to investigate Hoover and the bureau. He refused, saying he thought Hoover was doing a fine job. His refusal was a surprise for those who regarded him as the greatest congressional defender of the Constitution.

Later developments kept alive the call for an investigation of the FBI. Eventually, congressional investigations were inevitable because of the perseverance of NBC reporter Carl Stern. A year after the burglary, he asked the FBI to reveal what COINTELPRO was. The term was on one of the Media files. It was a mere routing slip, but it turned out to be the single most important file stolen. As a result of a lawsuit brought by Stern more than a year after the burglary, a federal judge ordered the FBI to hand over the papers that revealed the COINTELPRO operation: a series of dirty tricks and criminal operations to “expose, disrupt and otherwise neutralize” people Hoover considered subversive.

The details of these operations shocked the public in 1974. They ranged from crude to cruel — injecting activists’ oranges with strong laxatives, hiring prostitutes known to have venereal disease to seduce activists and clandestinely trying to convince Martin Luther King to commit suicide. Some operations led to murder, and some led to perjured testimony by FBI informers and agents that sent innocent people to prison for decades.

The details of these operations shocked the public in 1974. They ranged from crude to cruel — injecting activists’ oranges with strong laxatives, hiring prostitutes known to have venereal disease to seduce activists and clandestinely trying to convince Martin Luther King to commit suicide. Some operations led to murder, and some led to perjured testimony by FBI informers and agents that sent innocent people to prison for decades.

Thanks to the Media and subsequent revelations, there was a spirit of reform by the end of 1974. In January 1975 both houses of Congress voted to conduct the first congressional investigations of all intelligence agencies.

The hearings conducted by the Senate’s Church Committee, named for its chair, Senator Frank Church of Idaho, mattered most. During those hearings the public heard intelligence officials testify under oath about the cruel things done, and the lawlessness in Hoover’s FBI. Reforms were enacted, including establishment of the first intelligence oversight committees in Congress. Perhaps the most important reform that emerged was the strengthening in 1974 of the Freedom of Information Act. Though the bureau often is slow to obey, that reform led to the release of hundreds of thousands of files that continue to reveal the FBI’s secret history. It was learned, for instance, that for more than 20 years, the FBI had a formal program that involved 100,880 members of the American Legion, who worked as untrained informers, regularly supplied the FBI with written reports on people in their communities.

The bureau’s failure to find the Media burglars was deeply frustrating to Hoover. As bureau officials repeatedly stated in the record of the five-year investigation of the burglary, they never found any evidence or any witnesses with direct or indirect information about the burglars or the crime they committed.

Davidon was right. Presented with evidence of FBI’s suppression of dissent, the American people demanded action. Intelligence agencies were investigated and new policies established controls.

Now, Americans again have a choice about the future of their intelligence agencies. In response to the Snowden revelations, legislation moving through Congress has conflicting goals. Some bills would reduce the massive collection of data and other invasive techniques. Other bills would protect and even expand invasive techniques. It is unclear where Americans stand this time. Will they demand a halt to excessive overreach by intelligence agencies, as they did in the 1970s, or will they accept and endorse continued excessive overreach?

Betty Medsger is head of the journalism education program at San Francisco State University, where she founded the Center for the Integration and Improvement of Journalism. She is a founding member of Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE).