Carlos Blanco Aguinaga (1926-2013): An exile’s fiction

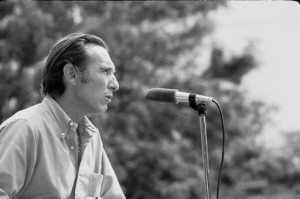

Carlos Blanco Aguinaga at the Thurgood Marshall College opening ceremony on September 26, 1970. Photo courtesy UCSD.

Carlos Blanco Aguinaga, a preeminent scholar of Spanish literature, a refugee of the Spanish Civil War, and a great friend of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and ALBA, died on September 11. A prolific, rigorous and charismatic scholar, he helped reshape the field of Hispanic Studies in the United States and Spain.

Carlos Blanco was born in 1926 in Irún, on the Spanish side of the Basque Country. In September 1936, as the Nationalist General Emilio Mola and his forces fought Republican troops for control of the town, Blanco Aguinaga and his family walked across the international bridge into Hendaye, France. While his father worked for the Spanish Republic from Hendaye, Blanco Aguinaga’s family integrated into life in France. But in 1939, with the fall of Madrid to the Nationalists imminent and the sense that their adopted country could not withstand a Nazi invasion, Blanco Aguinaga’s father went into exile in Mexico. After a three week passage on the ship Orinoco, 12-year-old Blanco Aguinaga, his mother, and his sister joined their father for their second exile, arriving in Veracruz, Mexico on August 21, 1939.

Although Blanco Aguinaga’s family integrated into Mexican life as best they could, they imagined they were only in Mexico temporarily, until Franco fell. In fact, Blanco Aguinaga would spend the next 74 years in exile. After attending Spanish Republican schools in Mexico City, Blanco Aguinaga moved to the United States to attend Harvard when he was 16 years old. There he studied Spanish writers such as Miguel de Unamuno and Antonio Machado, banned in schools controlled by Franco. He returned to Mexico for his post-graduate education and began a life-long career as a writer and literary scholar. Professorships at various universities in the United States led Blanco Aguinaga to the University of California, San Diego, where he was Professor Emeritus of Spanish Literature until his death last September.

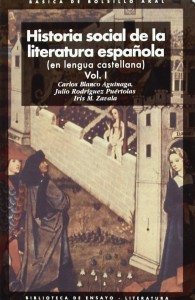

Blanco Aguinaga alternated between literary criticism and creative work throughout his life. He worked on Golden Age authors Francisco Quevedo and Miguel de Cervantes, studied the poetry of his fellow Spanish exile Emilio Prados, and wrote a definitive two-volume text on the social history of modern Spanish literature. In the 1980s, Blanco Aguinaga turned his attention to fiction, publishing five novels and one collection of short stories between 1984 and 2000. In three of these creative works, Blanco Aguinaga focuses on stories that parallel his own: the disjointed path of the Spanish exile to Mexico.

Carretera de Cuernavaca (1990) is a collection of short stories that follow different characters before, during and after their exile journeys from Spain to Mexico. In prose that is at times magical and at times starkly realistic, Blanco Aguinaga writes about the dilemmas and adjustments particular to Spaniards who were children when they left Spain. For Blanco Aguinaga’s characters, navigating the pitfalls of adolescence is more difficult away from one’s homeland, as is raising a family in which the children consider themselves Mexican while the parents consider themselves Spanish. The stories in Carretera de Cuernavaca beautifully capture the emotions and disorientation of exile.

For En voz continua (1997), Blanco Aguinaga re-creates a fictional version of Emilio Prados. The author imagines the poet reflecting on his deathbed about his life in Spain before and during the Spanish Civil War as well as his Mexican exile. Thinking through the confusing political situation in Spain before the war, the Prados character also struggles to fit into both Spanish and Mexican life as a writer and a homosexual. Through Prados, Blanco Aguinaga draws a portrait of the confusion and difficulty of belonging that is common to all exile experiences.

Blanco Aguinaga’s last work of fiction, Esperando la lluvia de la tarde: fábula de exilios (2000), combines a father’s memories with his son’s, both retelling their life stories simultaneously as the father nears death. Father and son are Spanish exiles of two different generations who exhibit profound differences in how they have navigated their lives while displaced from their home country. Major events of the 20th Century in Europe and the United States–the Spanish Republic, World War II, the “Red Scare” and the Watts riots in Los Angeles–are filtered through the perspectives of two men who have spent most their lives in exile.

Although Blanco Aguinaga’s fiction captures many of the author’s experiences and emotions of exile, the author recounted his own story in his autobiography, Por el mundo, published in 2007. He writes matter-of-factly that “of course the central facts of this story are clear: a well protected early childhood… ; a violent and long civil war … that we would end up losing; a difficult and painful early exile…; and then, a second exile to a remote and surprising country. This is all true, but what about the details?” In his fiction and his autobiography, Blanco Aguinaga succeeded in fleshing out these details, and in so doing created a rich narrative about a singular life.

Sara J. Brenneis is Assistant Professor of Spanish at Amherst College and author of Genre Fusion: A New Approach to History, Fiction, and Memory in Contemporary Spain (Purdue University Press, 2013).

I met Carlos Blanco as a student when we were involved in the formation of what was then know as Third College. He was the first truly internationalist person I had ever met. It is that aspect of his thought that has always stuck with me. I will always be and “international man”.

I first met Carlos Blanco through his articles on early modern Spanish literature–the picaresque novel, Cervantes, and the poet Quevedo. Although these were not his primary fields of research, Blanco’s articles were brilliant. They exposed me to a historical and dialectical way of thinking about culture that captured my imagination like no other scholarship or professor had done before. For a fledgling doctoral student, his writing left every other celebrated Hispanist in the dust. After I was lucky enough to be hired by Blanco at UC San Diego in 1986, I had the privilege to be his colleague for several years prior to his retirement. In my now thirty years of university teaching, I have never met a more magnetic, generous, insightful, and committed intellectual.

Goian Bego, Carlos Blanco Aguinaga, egun handira arte! Neure iaun maitea, ioan zatzaizkit lurretik, baiña ez gogotik, eta ez bihotzetik. Heldu nintzen. Ezterautazu iguriki. Ordea eneak dira faltak, enea da hobena. Gerotik gerora ibili naiz, eta hala dabillanari gerthatzen ohi zaikana egin zait niri ere.

EN EL PRINCIPIO

Si he perdido la vida,

el tiempo,

todo lo que tiré,

como un anillo,

al agua,

si he perdido la voz en la maleza,

me queda la palabra.

Si he sufrido la sed,

el hambre,

todo lo que era mío y resultó ser nada,

si he segado las sombras en silencio,

me queda la palabra.

Si abrí los labios para ver el rostro puro y terrible de mi patria,

si abrí los labios hasta desgarrármelos,

me queda la palabra.

(Blas de Otero.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eABVuX9eeDE

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2qPaRP9vggE

Eskerrik asko, moltes gràcies, moitas grazas, munches gracies, muitas gracias,fòrça gràcies, muchas gracias.